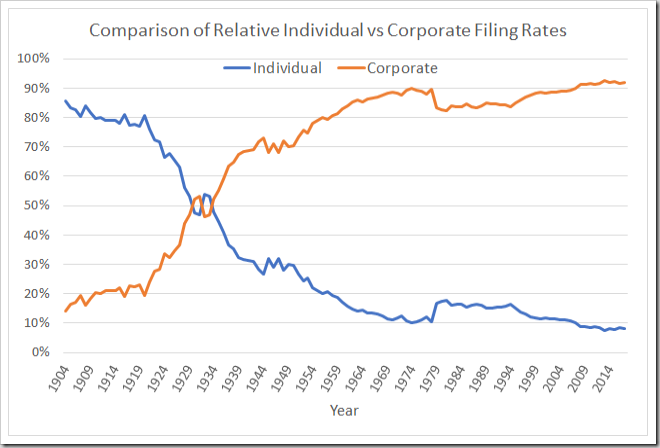

In the first year of operation of the Australian national patent system – 1904 – just over 1,200 patent applications were filed, more than 85% of which were lodged in the names of individual inventors, rather than companies. In 2017, by contrast, around 28,600 Australian standard patent applications were filed, of which just 10% named personal applicants – nowadays, 90% of all patent applications are filed by companies and other collective organisations. This observation naturally prompts the question: when did invention cease to be a predominantly individual activity, and become principally the product of corporate research and development?

In the first year of operation of the Australian national patent system – 1904 – just over 1,200 patent applications were filed, more than 85% of which were lodged in the names of individual inventors, rather than companies. In 2017, by contrast, around 28,600 Australian standard patent applications were filed, of which just 10% named personal applicants – nowadays, 90% of all patent applications are filed by companies and other collective organisations. This observation naturally prompts the question: when did invention cease to be a predominantly individual activity, and become principally the product of corporate research and development?With the release by IP Australia last week of the first stage of the 2018 Intellectual Property Government Open Data (IPGOD) it becomes possible to directly answer this question for Australian patent filings. For the first time, thanks to machine learning technology, every applicant on every application for all four registered IP rights (patents, trade marks, registered designs and plant breeder’s rights) is flagged as either an individual, or a corporate entity. In past years this information was only consistently available for patent records from around 1980, due to the more limited data that could be extracted from earlier record-keeping systems. By the 1980’s, over 80% of all patent applications were being filed each year by corporations rather than individuals.

In fact, the transition from consistently 80% or more personal filings to consistently over 80% corporate filings took place over a period of nearly four decades, starting in 1920. The final year in which more patent applications were filed by individuals than by corporations was 1933, and by the start of the second World War over two-thirds of patent applicants were corporations.

Historical records also clearly show the impact of international conflicts, and global and domestic economic events, on patent filing behaviour. A comparison using US patent data as a benchmark also shows that filings of Australian patent applications have historically tended towards strong growth, but relatively high volatility. In the 21st century, however, growth in Australian patent filings has clearly slowed relative to the US benchmark.

A History of Australia in Patent Filings

Below is an annotated chart of the number of Australian patent applications filed annually since the federal patent system was established in 1904. I have also included a plot of the worldwide total of national gross domestic product (GDP) since 1960, using data available from the World Bank.Clearly, the overall trend in patent filings over time has been upward. In the first half of the 20th century this growth was predictably slowed by the first World War, the Great Depression and the second World War. Comparison with global GDP data available from 1960 indicates that, very broadly speaking, growth in patent filings has tracked GDP growth. However, there are a few unique features of the Australian filing rates, including the effect of the early-90’s Australian economic downturn that then-treasurer Paul Keating called ‘the recession we had to have’, and the 2013 boost in filings (and subsequent dip in 2014) caused by the ‘Raising the Bar’ IP law reforms.

Less-readily explained, however, is a notable growth in Australian patent filings from around 1950 through to 1969, following which the annual number of applications fell dramatically. Indeed, the number of patent applications filed in Australian in 1978 (7,178) was just half the peak number of 14,228 filed in 1969. This number was not exceeded until 1990, and it was not until 1996 that the annual filing rate rose to be consistently above that 1969 high.

When I first plotted the Australian application numbers in isolation I thought that the 1970’s crash was the key feature, and wondered whether it might be connected with the relatively turbulent times surrounding the era of the Whitlam Labor government in Australia. Of course this might well be a factor, but I soon realised that the growth in filings that preceded the crash is just as difficult to explain. A comparison with historical US utility patent filings (using USPTO data) serves to illustrate the point.

As the above chart shows, following the second World War, the rate of growth of Australian patent filings significantly exceeded that of the US. While today there are around 20 times as many patent applications filed in the US each year as in Australia, in 1969 there were just seven times as many US applications filed. Additionally, the growth in US filings since 1960 is far more consistent with the general growth in GDP. It therefore seems that it is the acceleration in Australian patent filings between 1950 and 1969 that is the most anomalous feature of the data. In this context, the 1970’s collapse in filings might be regarded as a ‘correction’ – had the Australian filing rate followed the same pattern as GDP and/or US patent filings, it seems likely that it would have ended up in around the same place by the mid-1990’s. I am at a loss to explain this behaviour, so if you have any ideas please feel free to leave your thoughts in a comment below, or send me an email.

Of greater concern from the perspective of Australia’s current and future economic health is that while filing rates were generally tracking the US through most of the 1990’s (notably, perhaps, the early years of the Patents Act 1990, before successive governments began tinkering with the system), since around 2000 there has been a slow-down in the rate of growth of Australian filings relative to the US. Foreign applicants have made a significant contribution to growth in US patent applications during this period (according to WIPO data, 2009 was the first year in which the number of applications by non-residents exceeded the number of US resident applications). Yet even though non-residents are responsible for over 90% of Australian standard patent filings, growth in applications has not kept pace with the US, which might indicate that Australia is not seen as such a good investment by foreign patent applicants.

The ‘Corporatisation’ of Invention

A feature of the annual IPGOD data is the effort made to segment applicants into private individuals, small and medium enterprises (SME’s) and other corporate organisations. In the past, however, differentiating between private individuals and corporate bodies as patent applicants was only carried out for more recent records, for which there is sufficient structure in the data to distinguish between personal and corporate applicant names. For example, in the 2017 IPGOD release, patent records for which this distinction is made commence in January 1980.Prior to 1980, the only information available in many cases is a single text field containing the full applicant name, complete with any variations, typographical errors, or document scanning errors, that might have crept in over the years. A human reviewer might have relatively little difficulty in determining that ‘Adelaide Mary Swift’ is probably an individual, whereas ‘Sydney Steel Corp’ is probably a company name (even though ‘Corp’ can be a surname), although they might have more trouble with names in unfamiliar languages. However, with over 350,000 records in the pre-1980 data, conducting a manual review would be completely impractical.

Last year I developed a machine learning algorithm that I trained using millions of personal and company names drawn from US patent records, and other sources, to classify names as either ‘individual’ or ‘corporate’, which it can now do with greater than 99% accuracy. This year, I was engaged by IP Australia to (among other things) deploy this machine learning algorithm to classify all of the old name records back to the beginning of the federal patent system in 1904. This classification is now available in the new IPGOD release.

The chart below shows the annual breakdown of individual versus corporate applicants over time. The data is ‘stacked’, i.e. the corporate data sits ‘on top of’, rather than ‘behind’ the individual data. (Note that there are more ‘applicants’ than ‘applications’ each year because an application may name multiple co-applications, which may themselves be all individual, all corporate, or a mix of both.)

Since 1900, the world’s population has grown nearly five-fold, from 1.6 billion to 7.5 billion people, while Australia’s population went from just under 3.8 million in 1901 to 24.9 million today (according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics population clock). Meanwhile, the number of personal patent applicants has increased from 1921 in 1904 to 2562 in 2017, i.e. growth of just 2.8 times, which did not even keep pace with population growth, let alone the massive growth in corporate patenting that appears to characterise late- and post-industrial economic activity. Interestingly, whatever events caused the 1970’s downturn in patent applications appear to have affected individual applicants as much as corporate filings, despite the fact that there was no corresponding growth in applications by private individuals during the preceding two decades.

The chart below shows the relative proportions of individual and corporate patent application activity.

As can be seen, the majority of the transition from inventor-driven patenting to corporate patenting occurred between the first and second World Wars. In 1918, 78% of all patent applicants were private individuals. By 1939, 68% of applicants were corporate. The ‘crossover’ occurred during the 1930’s, when the Great Depression slowed growth in corporate activity, and enabled individual inventors to hold their own for a few years. But by 1934, when the corporate share of new applications topped 50% for the third time, the days of individuals filing more patent applications than corporations were gone forever.

While it is notable that economic downturns, and crises such as major wars, have a greater impact on corporate patenting activity than on personal filings, the data incontrovertibly shows that in a post-industrial society, invention and commercialisation are very much corporate activities. This should not surprise anyone. The ‘myth of the lone inventor’ has long stood on shaky ground, and so it is hardly a controversial idea that a collaborative environment, in which co-workers muster resources and share a common objective to succeed, is a more effective engine for invention.

Conclusion – Who Can Solve the Mystery of the ‘Filing Boom’?

Just as environmental changes and events are written into the growth rings of trees, the accretion of ice, and sedimentary rock layers, the impressions of Australia’s political and economic history for just over a century are clearly visible in the nation’s patent records. Many of the origins of these impressions are well-known, including two world wars and a number of global and national economic downturns. However, the causes of unprecedented growth in corporate patent applications in the decades following the second World War, and a subsequent crash in filings during the 1970’s are somewhat more mysterious – to me, at least.It might be useful to know the extent to which the ‘filing boom’ was driven by Australian and/or foreign applicants. Unfortunately, WIPO data on resident versus non-resident filings is available only back to 1980. The current IPGOD data does, in fact, include some data on national origin of applicants prior to 1980. However,as discussed in the postscript below, I do not consider this data to be a reliable source of insight.

For now, therefore, the ‘filing boom’ remains a mystery.

As I noted at the outset, the current IPGOD release is only the first stage for 2018. The information that is currently lacking includes company size data (i.e. SME/large) and agent/attorney information. IP Australia anticipates that the second stage, including this additional data, will be released in early July.

Postscript – On Applicant Country Data in IPGOD 2018

Every applicant for and Australian patent of course has a country of residence. This information is substantially complete for all records after about 1990, however prior to this the availability of country information is less consistent. My understanding is that this is a limitation of the source data, in that detailed applicant information is less readily available in older systems (including paper records, from the ‘pre-computer’ age). Nonetheless, earlier data has been included in the current IPGOD release, to the extent possible in view of these limitations.However, having been involved in this year’s data-matching work with IP Australia I am conscious that this data must be treated with caution. For older records without country information, a country of origin was determined only for applicant records that could be reliably matched with more recent data having associated country information. As a result, the proportion of IPGOD records including country information declines when going further back in time. Furthermore, there is a bias inherent in the older records for which country information exists, in that these reflect the particular set of earlier applicants that survived and continued to file patent applications into recent times.

The following chart shows the available annual resident versus non-resident filing comparison from 1950 to 1990, along with the fraction of records for which country information is available in each year. This indicates that, e.g., in 1950 the comparison is based on only 14% of all applicant records for which the IPGOD data identifies country-of-origin, whereas by 1990 the country information in the data set is substantially complete.

Unfortunately, this data may be largely useless as a means to identify any national or international drivers of the ‘filing boom’. It is quite possible that the boom was largely a result of filings by companies that may have exited the patent system during the subsequent 1970’s ‘bust’. Country information for any such applicants would therefore not be available for matching using more recent records. In other words, the data that we most need to see in an attempt to gain further insight into the origins of the filing boom is the data that is least likely to be available.

Tags: Australia, Economics, IPGOD, Patent analytics

0 comments:

Post a Comment