The former version of section 40 required, among other things, that a patent specification ‘describe the invention fully’, and that the patent claims defining the invention must be ‘fairly based on the matter described in the specification’. Over time, the courts interpreted these provisions as, in most cases, requiring only that the description should enable a person of ordinary skill in the relevant field to implement something falling within the scope of the claims without further invention, and should provide a ‘real and reasonably clear disclosure’ of the invention that is broadly consistent (or, at least, not inconsistent) with what is claimed. In practice, this was a pretty low bar that generally allowed applicants to make relatively broad claims despite possibly having disclosed only a single, specific, implementation of an invention.

By comparison, the current version of section 40 requires that a patent specification ‘disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art’, and that the claims must be ‘supported by matter disclosed in the specification’. The intended effect of these changes is, firstly, to require that the description provide sufficient information to enable the skilled person to perform the invention across the full scope of the claims and, secondly, that the scope of the claims should not be broader than is justified by the extent of the disclosure and the contribution made by the invention. While these intentions are not necessarily apparent from the wording of the provisions, the idea is that they are implied through the use of similar terminology to that used in other jurisdictions (particularly Europe and the UK), as indicated in the Explanatory Memorandum that accompanied the Raising the Bar legislation.

If the changes to the law achieve their intended effects, then the standard of disclosure required, and the concurrence of the relationship between the description and claims, should be substantially enhanced. I would have to say, however, that there is little in the first instance decision in Encompass v InfoTrack to indicate just how far the bar has been raised. This appears, at least in part, to be a result of the way the case was argued, which led the court to give greater attention to what the new provisions are not, rather than to what they are. In any event, it is to be hoped that consideration by the Full Court will be more enlightening.

Background – Encompass Targets InfoTrack with Innovation Patents

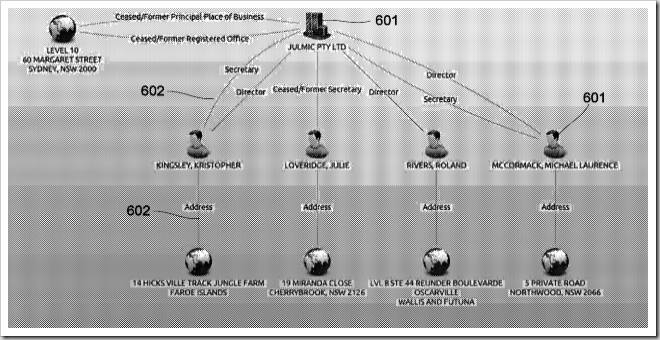

Encompass is the applicant of Australian standard patent application no. 2013201921, which relates to conducting searches across multiple disparate databases (such as motor vehicle, land titles, and company registries) when gathering business intelligence. The system disclosed in the patent specification does this by generating a graphical ‘network’ representation of related entities (e.g. companies, individual directors/executives, addresses and so forth), enabling the user to select one or more entities from the network, automatically identifying the relevant databases to search for information about the selected entity, and then conducting the required searches, including making any payments that are required to access information held in the databases.The standard patent application was filed, and examination was requested, on 25 March 2013, i.e. prior to the commencement of provisions in the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 that introduced more-stringent standards for the disclosure required in a patent specification to support the claims defining a patented invention. The application has been accepted, however it is currently under opposition by InfoTrack.

Encompass’ Federal Court infringement action against InfoTrack is based on two innovation patents, nos. 2014101164 and 2014101413, that were divided from the standard application (making it their ‘parent application’) on 19 September 2014 and 28 November 2014, respectively. As anyone familiar with Australian patent litigation practice will be aware, dividing one or more innovation patents from a pending standard patent application, to rapidly obtain an enforceable right with claims targeting infringing acts, has become a fairly common strategy. Indeed, this strategic use of innovation patents was one of the factors that influenced the Australian Government’s Productivity Commission to recommend that the innovation patent system be abolished in its Report on the nation’s IP Arrangements.

How the Innovation Patents’ Claims Were Narrowed

In the original parent application, the claims (which have since been amended) referred only to ‘generating a network representation’ and displaying it to a user, e.g. as shown in Figure 6 of the patent specification reproduced below.

In the divisional innovation patents, and in the amended parent application, however, the claims recite ‘generating a network representation by querying remote data sources’. Notably, the patent specifications describe querying and/or searching data located in both ‘local’ and ‘remote’ data sources. For example, paragraphs [0153] and [0154] of the original (parent) patent specification, which are also present in the divisional innovation patents, make the following disclosure:

[0153] The system typically implements a data integration tier provides the integration to perform the data request and response activities from within the visualisation solution. To achieve this the processing system 210 utilizes "Client Adaptor" components that are configured for each data source and are responsible for translating the data received from the request and applying it to the visualisation model. This allows the processing system 210 to consume various types of data from local or remote hosting via Web Services, or relational database access and file system locations.

[0154] The Client Adaptors are a key component for integrating with data sources. The Client Adaptors can be configured to access any format of data storage; …

On the face of it, therefore, the specification is, at least arguably, asserting that it is an advantage of the disclosed system that it is completely agnostic as to the location and format of the data sources, as a result of its implementation using the ‘Client Adaptors’. As such, the specification does not suggest that there is anything special about generating the network representation using ‘remote’ versus ‘local’ sources of data.

Is There a Problem with Narrowing Patent Claims?

It is not clear why the ‘remote data sources’ limitation was included in the claims of the innovation patents – particularly given the specifications’ indifference to the locations of the sources of data. There was no such limitation in the claims of the parent standard application as filed, nor as subsequently accepted. It is, however, of note that the court found the inventions’ ability to search multiple remote data sources, as well as its ability automatically to make payments for data where required, to be features that distinguish the claims from the prior art relied upon by InfoTrack in the litigation.Inclusion of a requirement in the claims of the innovation patents that the network representation be generated by ‘querying remote data sources’ makes this an essential feature of the invention that was not present in the claims of the parent application, and that is not clearly identified as an essential feature in the description. The court agreed that the innovation patent specifications were ‘indifferent as to whether the data sources need to be remote or local’ and that ‘[a]s disclosed, the querying of “remote data sources” is not an essential part of the invention yet the invention as claimed has this moderately limiting feature’ (at [155]).

The ‘remote data sources’ requirement is a narrowing variation on the original (parent) claims that is not inconsistent with what is described in the specification (which, as the court noted, is agnostic as to whether the data sources are ‘local’ or ‘remote’). It should therefore be relatively uncontentious for me to assert that would be a legitimate variation under the fair basis test in the pre-Raising the Bar version of section 40. Indeed, precisely this issue arose in an opposition to the corresponding amendment requested in the parent standard patent application, which is subject to the former version of the Act, in which the hearing officer recently found that claims including the ‘querying remote data sources’ limitation are fairly based on the description: InfoTrack Pty Limited v Encompass Corporation Pty Ltd [2018] APO 16.

The question which arises is therefore whether a narrowing variation of this kind – i.e. one that is not inconsistent with the disclosure in the patent specification, but which plainly makes a particular feature essential to the invention in the absence of any indication in the specification as to how or why that limitation is significant – is permissible under the post-Raising the Bar version of section 40?

InfoTrack’s Invalidity Arguments

Based on the judgment, it appears that InfoTrack’s argument in relation to invalidity of the Encompass claims under section 40 might broadly be characterised as follows:- the claims would not have been valid under the ‘full description’ and ‘fair basis’ provisions of the former version of section 40;

- the Raising the Bar reforms represented a ‘strengthening’ of the requirements;

- therefore, the claims must also be invalid under the current version of section 40.

The Court’s Response

The court rejected InfoTrack’s arguments primarily on the basis of its finding that no remnant of the former ‘full description’ and ‘fair basis’ requirements survived the Raising the Bar reforms.Firstly, the court found (at [165]-[167]) that the obligation in paragraph 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act for the complete specification to ‘disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art’ is purely an enablement requirement, and contains no residual requirement to ‘make the nature of the invention plain’.

Similarly, with regard to the ‘support’ requirement in subsection 40(3), the court did not accept ‘that the former law about fair basis has any continuing vitality with respect to the new provision’ (at [171]).

Thus InfoTrack’s argument failed on its own terms, without the court even needing to consider whether the underlying proposition, i.e. that the claims would have been invalid under the provisions of the former section 40, was itself true. Personally, I think that InfoTrack would have failed on this basis as well – an opinion that is supported by the fact that it did indeed fail to establish that the claims do not satisfy the former requirements in its opposition to amendment of the parent standard patent application.

So, Has the Bar Been Raised?

In considering the application of the new paragraph 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act, requiring the complete specification to ‘disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art’, the court gave fairly extensive consideration (at [158]-[165]) to the changes made by the Raising the Bar Act and the intentions expressed in the Explanatory Memorandum. The conclusion that this is now purely an enablement provision, that contains no remnant of the former ‘full description’ requirement is, I think, correct. There was, ultimately, no dispute that the claims were enabled by the description, which I also happen to think is correct, although in the absence of disagreement over this issue the court did not need to address the more specific question of whether enablement was provided across the full scope of claims.As to the ‘support’ requirement in subsection 40(3), again I would agree with the court that the old ‘fair basis’ requirement has no ongoing relevance. However, I also note that the court stated (at [168]) that:

Section 40(3) of the Act requires that the claims ‘must be clear and succinct and supported by matter disclosed in the specification’. If this means what it appears to say then I do not doubt that the claims in the Patents satisfy this requirement. (Emphasis added.)

The fact is, however, that we know that the provision does not mean (only) what it appears to say. As noted in the Explanatory Memorandum:

This item is intended to align the Australian requirement with overseas jurisdictions’ requirements (such as the UK). Overseas case law and administrative decisions in respect of the ‘support’ requirement will be available to Australian courts and administrative decision-makers to assist in interpreting the new provision.

The court, in this instance, did not consider any of the ‘overseas case law’ or ‘administrative decisions’ that could assist it in interpreting the current subsection 40(3). Had it done so, I suspect the question of whether or not the claims satisfy the ‘support’ requirement would have been a lot less clear-cut. The practice of the European Patent Office in relation to support, for example, is rather strict, and I would suggest that a request to amend a European patent application to claim the use of only ‘remote data sources’, where the description is agnostic to the locations of the data sources, could well be refused.

In Encompass, however, the court did not consider the substantial body of UK case law and EPO decision-making in deciding that the claims-at-issue satisfy the ‘support’ requirement of subsection 40(3). It therefore remains an open question whether, and to what extent, the bar has been raised in this respect.

Conclusion – Will the Full Court Provide Clarification?

In its consideration of the amended provisions of section 40 of the Australian Patents Act, the Federal Court has (I think rightly) found that the former requirements for ‘full description’ and ‘fair basis’ have been completely replaced by the new ‘enablement’ and ‘support’ requirements. As such, the old case law on these provisions has no continuing relevance to patents and applications to which the new law applies.However, in Encompass, the court has made no progress on the task of developing new Australian case law in relation to the post-Raising the Bar provisions. As such, we are not much closer to discovering exactly how far the bar has been raised in relation to the standard of disclosure required in a patent specification. In particular, we are still waiting for the court to address the following questions:

- Is there a requirement in paragraph 40(2)(a), as the Explanatory Memorandum indicates despite the lack of express wording in the provision, that the description ‘enable the whole width of the claimed invention to be performed by the skilled person without undue burden, or the need for further invention’ and, assuming so, how is this assessment to be carried out?

- How ‘close’ is the correspondence required between the description and the claims in order to satisfy the ‘support’ requirement in subsection 40(3), and how is the comparison to be made?

Tags: Australia, Enablement, Law reform, Raising the Bar, Support

0 comments:

Post a Comment