I have previously expressed the opinion here that the patent troll problem is primarily one of litigation abuse, rather than patent abuse (see, e.g., earlier articles on why trolls are largely a US phenomenon, and why the Australian system is less conducive to their nefarious business models). Previous US attempts to curb troll activity, such as the proposed Saving High-Tech Innovators from Egregious Legal Disputes (SHIELD) Act of 2013 [PDF, 248kB], and its predecessor of 2012, have generally made the mistake of focussing on the technology to which the patent applies and/or the nature of the patent holder.

I have previously expressed the opinion here that the patent troll problem is primarily one of litigation abuse, rather than patent abuse (see, e.g., earlier articles on why trolls are largely a US phenomenon, and why the Australian system is less conducive to their nefarious business models). Previous US attempts to curb troll activity, such as the proposed Saving High-Tech Innovators from Egregious Legal Disputes (SHIELD) Act of 2013 [PDF, 248kB], and its predecessor of 2012, have generally made the mistake of focussing on the technology to which the patent applies and/or the nature of the patent holder.But a troll is defined by its actions, not by its corporate identity, the history of its patents, or the technology to which those patents apply.

Republican Congressman Bob Goodlatte apparently gets it. On 23 October 2013 he introduced the proposed Innovation Act 2013, which he describes as a patent litigation reform bill. The bill is technology-neutral and, as the Congressman’s media release explains:

…targets abusive patent litigation behavior and not specific entities with the goal of preventing individuals from taking advantage of gaps in the system to engage in litigation extortion. It does not attempt to eliminate valid patent litigation.

In the past week I have read numerous responses to the Goodlatte bill. A few have been relatively neutral, and simply set out the various provisions of the bill. Others raise a number of the issues which have previously caused me to express some scepticism as to whether the US would be willing to take the action necessary to rein in patent trolls. Over at the IAM Magazine Blog, Joff Wild rightly points out that the bill is not specifically ‘anti-troll’, but will affect the risks and obligations faced by patent plaintiffs generally. Andrew Williams, writing on the PatentDocs blog, describes the proposed legislation as a ‘blunt instrument that will impact all patent infringement actions’. The Innovation Alliance, which largely represents smaller innovators and patent owners, has also been critical of the bill.

None of this surprises me. I have previously expressed my opinion that there is no way to curb trolls without impacting the rights of patent-holders more generally. The goal must be to strike the right balance, not to try (and fail) to be all things to all people.

Tags: Law reform, Patent law, Trolls, US

According to

According to  I have it on good authority (two independent sources, just like a proper journalist) that the Director General of

I have it on good authority (two independent sources, just like a proper journalist) that the Director General of  It has been

It has been  The

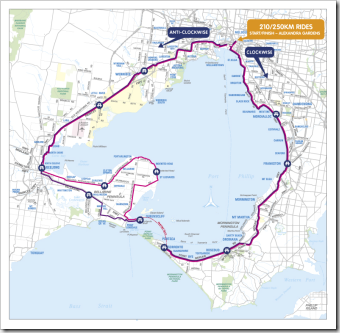

The  Tomorrow (i.e. Sunday 20 October 2013) I am going for a bike ride. That is not news in itself, since it is something I do most weekends. However, tomorrow’s ride is a bit longer than usual – 250 km (that is about 155 miles in non-metric units, or nearly 1250 furlongs for those gearing up for the Spring Racing Carnival here in Melbourne).

Tomorrow (i.e. Sunday 20 October 2013) I am going for a bike ride. That is not news in itself, since it is something I do most weekends. However, tomorrow’s ride is a bit longer than usual – 250 km (that is about 155 miles in non-metric units, or nearly 1250 furlongs for those gearing up for the Spring Racing Carnival here in Melbourne). On 30 August 2013, Justice Middleton in the Federal Court of Australia

On 30 August 2013, Justice Middleton in the Federal Court of Australia  This is, nominally, a blog about patents. But I like to think that it is a bit more than that – I endeavour, when I can, to write about the role of patent law, practice and policy in a broader social context. I believe strongly in the importance of discovery and innovation to the prosperity and improvement of individuals, communities, nations and humanity at large, and therefore that the ways in which we encourage and foster these activities are also vitally important.

This is, nominally, a blog about patents. But I like to think that it is a bit more than that – I endeavour, when I can, to write about the role of patent law, practice and policy in a broader social context. I believe strongly in the importance of discovery and innovation to the prosperity and improvement of individuals, communities, nations and humanity at large, and therefore that the ways in which we encourage and foster these activities are also vitally important. A $4 million investment by Samsung Ventures Investment Corporation in New Zealand company PowerbyProxi Limited has received wide coverage over the past week (see, e.g., the

A $4 million investment by Samsung Ventures Investment Corporation in New Zealand company PowerbyProxi Limited has received wide coverage over the past week (see, e.g., the