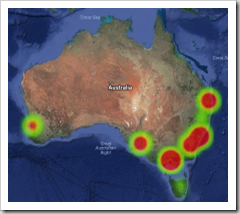

According to IP Australia data covering patent applications filed during a 16-year period commencing on 1 January 2000, Melbourne is the biotechnology capital of Australia. Sydney comes in second, followed by Brisbane. There is significant biotechnology activity in Adelaide and, to a lesser extent, Perth. Canberra looks to be an active area, but is something of a special case. There is, however, very little activity in this sector in Australian regional areas.

According to IP Australia data covering patent applications filed during a 16-year period commencing on 1 January 2000, Melbourne is the biotechnology capital of Australia. Sydney comes in second, followed by Brisbane. There is significant biotechnology activity in Adelaide and, to a lesser extent, Perth. Canberra looks to be an active area, but is something of a special case. There is, however, very little activity in this sector in Australian regional areas. A ‘heat map’ highlighting the locations of organisations filing Australian patent applications relating to developments in biotechnology shows how innovation in the biological sciences thrives principally where there is an ecosystem of academic, medical and corporate organisations located in close proximity. Melbourne’s leading position is driven primarily by the critical mass of public and private medical and bioscientific research institutes located in the ‘Parkville precinct’ and its immediate surrounds. Similarly, the primary origins of patent applications relating to biotechnology in the other capital cities coincide with the locations of major research universities, hospitals and associated companies and institutes.

The single largest filer of patent applications over the period analysed is – as in many other fields of technology – the Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). In fact, CSIRO is almost single-handedly responsible for putting Canberra on the map in biotech, as a result of the fact that it uses its national capital address on all patent applications. However, much of the actual research covered by those applications is conducted at CSIRO’s many other sites around Australia, including locations in and around Melbourne in Parkville, Clayton, Werribee and Geelong. In all likelihood, therefore, Melbourne’s leading position in Australian biotechnology research and development is even more pronounced than the map suggests.

The top Australian patent attorney firm handling all of these applications is Davies Collison Cave – and it is so by a considerable margin. Second-placed FB Rice has been responsible for filing only about half as many applications relating to biotechnology over the same period.

Defining ‘Biotechnology’

As in a number of recent articles (e.g. about the use and abuse of the innovation patent system, the woes of self-represented patent applicants, the fate of business method patent applications, and attorney firm market share) I have used the publicly-available Intellectual Property Government Open Data (IPGOD) 2016 data set to analyse ‘biotechnology’ patent-filing activity by Australian residents over a 16-year period commencing on 1 January 2000 and ending on 31 December 2015.The chosen starting-date is somewhat arbitrary. On the one hand, I wanted a ‘snapshot’ that is broadly representative of current activity in the field, for which a relatively short recent period is obviously most appropriate. On the other hand, taking too short a period does not yield sufficient data to produce an interesting or useful visualisation. Commencing at the turn of the millennium appears to be a reasonable compromise, in the sense that choosing a shorter period does not seem to significantly alter the general geographic distribution of applicants.

The applications to be included in my dataset were selected on the basis of their classification (either primary or secondary) under the International Patent Classification (IPC) system. Unfortunately, the IPC does not group ‘biotechnology’ under a specific section, class or subclass. Rather, particular applications of biotechnology are grouped within the categories of the technical fields in which they are applied. Thus, groups and subgroups covering aspects of biotechnology are to be found across the IPC, in classes such as those relating to plant and animal production (A01H and A01K), preservation, treatment and handling of foodstuffs (A23L), medical preparations (A61K), water treatment (C02F), organic chemistry and biochemistry (selected groups within C07 and C12) classes, test and measurement (selected groups within G01N), and bioinformatics (G06F19).

‘Biotechnology’ is thus quite broadly defined, and encompasses applications in agriculture, healthcare, food production, and hygiene, among other things.

Selecting on the basis of classification implies that only those applications that have been classified can be included, i.e. published standard applications and innovation patents. Provisional applications are not subject to classification, and are therefore not included as distinct filings in the data set. However, I selected only those patents and applications have a priority date on or after 1 January 2000 which, in most cases, was the date of filing of an initial provisional application. However, provisional filings that did not result in a subsequent Australian standard or innovation patent filing (either directly, or as the national phase of a PCT application) are not reflected in any way in the data set.

The Map

The ‘heat map’ below represents the geographic origins of all Australian patent applications in my data set (i.e. the location of the applicant organisation, as accurately as can be determined from the IPGOD data). The more applications originating from within a region, the more ‘intense’ the colour – with red being more intense, or ‘hotter’, and green being less intense, or ‘cooler’. Where an application has multiple joint applicants, it is counted multiple times such that each applicant’s location contributes to the heat map.It is immediately apparent, from the size of the red circles, that the hottest spot in Australia for biotechnology development and patenting is centred on Melbourne. By panning and zooming around the map, you can explore the hot zones in more detail, and see exactly where the greatest intensity of activity is to be found within each region.

A Few Observations

Zooming in on Melbourne, four main centres of activity are revealed. The first, and most intense (indeed, the most intense across the entire country) is centred on the Parkville precinct, which is home to The University of Melbourne (including the Bio21 Institute), the Royal Melbourne Hospital, Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital, as well as the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, CSL, the Doherty Institute, and many others. To the north-west is a second hotspot near the airport, centred on Agriculture Victoria Services. To the south-east is a more diffuse region around Monash University and the Monash Medical Centre. Finally, to the north-east is a further diffuse region encompassing La Trobe University, the Austin Hospital and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research. In addition to these four regions, there are numerous further spots of activity dotted around the city, suburbs and surrounding region.Similar patterns are to be found in the other active state capital cities. In Sydney, the greatest intensity of activity is to be found around Darlinghurst (home to the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, the St Vincent’s Centre for Applied Medical Research and the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute), in the vicinity of the Australian Technology Park, in the south-east around the University of NSW, and at Macquarie University and surrounds in the north. In Brisbane the main epicentres of activity are the University of Queensland and the Queensland University of Technology. In Perth, most activity is located around the University of Western Australia and the hospitals to its north-east, while much of the activity on Adelaide can be attributed to the University of Adelaide, along with the companies Medvet and Bionomics.

Outside the capital cities there is very little activity to be seen. In NSW there is some action in the vicinity of the University of New England in Armidale, and around the Department of Primary Industries in Orange. In Tasmania there is a fun little patch west of Launceston occupied by Tasmanian Alkaloids Pty Ltd, whose work relates to the effective extraction of opiates from poppies – a particular Tasmanian industry that is one of Australia’s largest and most unique (legal) contributions to the pharmaceutical industry.

Please explore the map, and share your own observations in the comments below. Having lived much of my life in Melbourne, and spent many years living and working around the Parkville area, I have no doubt that many readers are better able to do justice to the work going on in other regions of the country.

Top Applicants and Agents

I do not want to focus too much on numbers here. In view of the somewhat arbitrary selection of time period, and of IPC classes, there is not much that can meaningfully be said about absolute levels of activity. Rather, it is the relative levels within different regions, subject to these choices, that are of greatest interest.However, since the heat map does not ‘name names’, for interested readers here are a couple of charts showing the relative filing numbers of the top 20 patent applicants, and the top 20 patent attorney firms that represent them. By clear margins, CSIRO is the top applicant, and Davies Collision Cave the top firm.

Conclusion – Synergy in Numbers

Biotechnology, particularly as defined by the range of IPC classes selected in this analysis, has application in many fields. I therefore do not find it surprising that research, development and patenting activity tends to concentrate in areas where a ‘critical mass’ of cross-disciplinary resources and participants are able to come together. In this regard, the ‘Parkville precinct’, built around Melbourne University and the city’s major public hospitals, seems to be a particular Australian success story.While this kind of synergistic effect is well-recognised, efforts by governments and other organisations to artificially synthesise new technology precincts are generally unsuccessful. This may be because too often such projects are waylaid by tangential considerations, such as locating a technology park in an outer suburban or regional area where land is plentiful and cheap, and there is some political mileage to be gained by trying to ‘stimulate’ the local economy. Nobody would suggest that land is cheap in inner-city Parkville, or that the area requires an economic stimulus. However, I can say from experience that it is a great area in which to live and work, now dominated by institutions and companies that I am sure have no trouble attracting top people.

The bottom line is that there is a handful of biotech ‘hotspots’ dotted around the country. They may not, for the most part, be located so as to satisfy other political objectives such as regional development or winning votes in marginal electorates. But if patenting activity is any measure of success, then they are doing something more important – actually working!

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment