In an eight year period – one full innovation patent lifecycle – between 2007 and 2015, Australian residents were overwhelmingly the biggest users of the second-tier innovation patent system, filing over 10,000 innovation patent applications. The next most frequent filers were the Chinese, with just 1500 applications, followed by US applicants with less than 1000. Over 90% of the Australian applicants were individuals or small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs – businesses with fewer than 200 employees), i.e. the exact people the innovation patent system was intended to benefit when it was established by the Howard Government in 2001. Over the same period, Australian residents filed just over 23,000 standard patent applications, a very distant second to US residents who were responsible for 115,000 applications.

In an eight year period – one full innovation patent lifecycle – between 2007 and 2015, Australian residents were overwhelmingly the biggest users of the second-tier innovation patent system, filing over 10,000 innovation patent applications. The next most frequent filers were the Chinese, with just 1500 applications, followed by US applicants with less than 1000. Over 90% of the Australian applicants were individuals or small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs – businesses with fewer than 200 employees), i.e. the exact people the innovation patent system was intended to benefit when it was established by the Howard Government in 2001. Over the same period, Australian residents filed just over 23,000 standard patent applications, a very distant second to US residents who were responsible for 115,000 applications.Yet despite the system’s success by these measures, it is an open secret that IP Australia would like to see the end of the innovation patent, and has been diligently working behind-the-scenes for some years to achieve this objective. After first proposing – and failing to win substantive support for – raising the ‘innovative step’ threshold to the same level of inventiveness required for standard patents, IP Australia economists undertook a study of the ‘economic impact’ of the innovation patent system which was used – prior to any publication or consultation on the methodology or results – to convince the now-defunct Advisory Council on Intellectual Property (ACIP) to issue, as its final act, a recommendation that the Government consider abolishing the system. A belated consultation on this recommendation elicited submissions from a range of stakeholders who once again overwhelmingly supported retaining the innovation patent as a second-tier right in Australia, although many favoured modifying the system to address problems that had become apparent since its introduction in 2001. IP Australia passed the submissions received in response to its consultation paper on to the Productivity Commission, which was by then in the midst of a 12-month review of Australia’s entire IP system. To nobody’s great surprise, the Commission recommended abolition of the innovation patent system, in both its draft report and, despite further submissions from stakeholders, in its final report.

More recently, Innovation and Science Australia released its Performance Review of the Australian Innovation, Science and Research System, in which it followed the Productivity Commission in declaring that Australia grants patent protection too easily and this has allowed a proliferation of low-quality patents, and innovation patents in particular. IP Australia was quick to highlight this particular ‘weakness’ of the IP system in a post on its blog.

Now, I do not doubt that IP Australia would dispute that it is gunning for the innovation patent. Rather, I am sure that its position is that it is seeking to provide evidence-based input to government to enable it to make informed decisions in meeting legitimate policy objectives. The difficulty I have with this is that, despite a veritable cacophony of dissenting views from stakeholders, with proposals to improve rather than abolish the innovation patent system, it seems that the current position of IP Australia, the Productivity Commission, and Innovation and Science Australia – all of which have the Government’s ear – is informed almost entirely by the IP Australia Economic Impact study. It is perhaps worth noting that this study cannot be independently replicated, verified and/or its assumptions tested, because key data on which it is based – Australian Tax Office records of R&D tax concession claims by businesses, industry sector information, and business/tax registration records – are not publicly available.

There is, however, much in the Economic Impacts study itself, and in the publicly-available IPGOD data set, supporting a view that the innovation patent system has not failed so badly as to justify its abolition. Although its fate may already be sealed, given the forces rallying against it, it is worth taking a fresh look at who is using the innovation patent system and, equally importantly, who is abusing it.

Data for Analysis

The innovation patent system was created in 2001, and the IPGOD 2016 data set ends on 31 December 2015. Rather than look at this entire period, I have elected to extract data for applications filed between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2015. There are a number of reasons for this choice:- it represents a period just a little shorter than the ten years covered in my previous analyses of patent attorney services and examination outcomes, enabling a broad comparison of data from the three articles;

- it encompasses one complete ‘innovation patent lifecycle’ (innovation patents have a maximum term of eight years, although for various reasons noted later the data towards the end of my nine-year span is incomplete or otherwise unrepresentative); and

- it avoids the early transitional years of the new system, during which applicant behaviour may not yet have stabilised.

Filing Statistics

Top Innovation Patent Filers, 2007-2015

The table below summarises the top 30 applicants for innovation patents over the 2007-2015 period, including country of residence. The single biggest user of the Australian innovation patent system is not Australian at all – it is Apple, Inc. I have written about this strategic use of the system previously, both here on Patentology and for IP Watchdog. With the exception of the UK’s fancy vacuum cleaner, bladeless fan, and hairdryer maker Dyson, the top 30 filing list is dominated by US, Chinese and Australian applicants. I will have more to say about the Chinese later, in relation to abuses of the system!

Rank

|

Applicant Name

|

Country

|

No.

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | APPLE | US | 201 |

| 2 | HENGDIAN GROUP LINIX MOTOR CO | CN | 147 |

| 3 | GONG, ZHU | CN | 65 |

| 4 | ZHEJIANG LINIX MOTOR CO | CN | 60 |

| 5 | HENGDIAN GROUP INNUOVO ELECTRIC CO | CN | 60 |

| 6 | MACAU UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECH | MO | 48 |

| 7 | GENERAL ELECTRIC CO | US | 48 |

| 8 | INNOVIA SECURITY | AU | 46 |

| 9 | ARISTOCRAT TECH AUSTRALIA | AU | 46 |

| 10 | CHERVON | CN | 42 |

| 11 | INNUOVO INTL TRADE CO HENGDIAN GROUP | CN | 40 |

| 12 | DONGYANG LINIX MACHINE ELECTRICITY CO | CN | 40 |

| 13 | MACAU UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE & TECH | CN | 38 |

| 14 | NOVARTIS | CH | 33 |

| 15 | US | 32 | |

| 16 | DYSON TECH | GB | 31 |

| 17 | ILLINOIS TOOL WORKS | US | 31 |

| 18 | HEVAL HENGDIAN MACHINERY CO CNNC | CN | 28 |

| 19 | TONGXIANG CITY AOPEIOU GARMENTS CO | CN | 27 |

| 20 | GERARD LIGHTING | AU | 26 |

| 21 | CORNING CABLE SYSTEMS | US | 25 |

| 22 | LINC ENERGY | AU | 23 |

| 23 | SUFA HENGDIAN MACHINE COCNNC | CN | 23 |

| 24 | EMERSON ELECTRIC CO | US | 22 |

| 25 | CSR BUILDING PRODUCTS | AU | 22 |

| 26 | ZHEJIANG LINIX SOLAR CO | CN | 20 |

| 27 | WISETECH GLOBAL | AU | 20 |

| 28 | BREVILLE | AU | 20 |

| 29 | ZHEJIANG JINGUANG SOLAR TECH CO | CN | 20 |

| 30 | NINGBO SHI JIANGDONG QU DAKOU TRADING CO | CN | 19 |

Certification Statistics

Top Innovation Patent Certifiers, 2007-2015

Innovation patents are granted without substantive examination to determine whether the claimed invention is actually patentable. Requesting examination is optional, however the patent cannot be enforced, or used as the basis for a threat of enforcement, unless it is successfully examined and certified. Certification is therefore generally a better indicator of actual relevance and value of the patent to a business than mere filing and grant.The table below summarises the top 10 certifiers of their innovation patents over the 2007-2015 period. Apple is once again at the top of the list, and it is notable that those companies that have obtained significant numbers of certified innovation patents tend to request examination of the majority of applications that they file.

Businesses like this should, in my view, generally be regarded as the ‘real’ users of the innovation patent system, against which its success or otherwise should be assessed. Half of the companies on this list are Australian. None are Chinese.

Rank

|

Applicant Name

|

Country

|

No.

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | APPLE | US | 168 |

| 2 | INNOVIA SECURITY | AU | 42 |

| 3 | ARISTOCRAT TECH AUSTRALIA | AU | 39 |

| 4 | DYSON TECH | GB | 28 |

| 5 | NOVARTIS | CH | 20 |

| 6 | GERARD LIGHTING | AU | 20 |

| 7 | BREVILLE | AU | 17 |

| 8 | UNILOC USA | US | 16 |

| 9 | SRG ENTERPRIZES | AU | 13 |

| 10 | ABBVIE IRELAND UNLIMITED CO | IE | 12 |

Apple

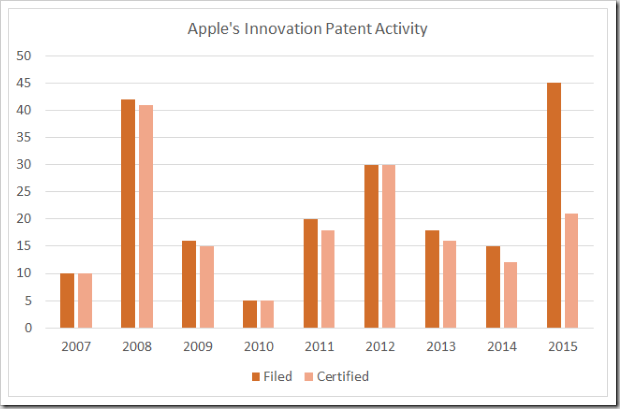

In my earlier articles mentioned above – published way back in 2012 – I noted Apple’s bolstering of its enforceable Australian patent portfolio via innovation patent filing and certification in the years leading up to what became an extended period of litigation against Samsung. The chart below shows Apple’s annual rates of filing for innovation patents, along with the corresponding number of those patents that have been certified.

While there was a decline in Apple’s activity during the ‘Samsung’ years of 2013 and 2014, somewhat surprisingly Apple filed its largest number of innovation patents ever in the year following its global (except for the US) settlement of that dispute. While it appears from the chart that the certification rate is lower for the 2015 filings, this is possibly merely an artefact of the delay between filing/grant and examination/certification. Many of the innovation patents filed in 2015 would not have had sufficient time to progress through the examination process by 31 December 2015, when the IPGOD 2016 snapshot was taken.

This all makes one wonder what future plans Apple may have for enforcement in Australia. Or perhaps it is a deterrence strategy.

Australian Filers

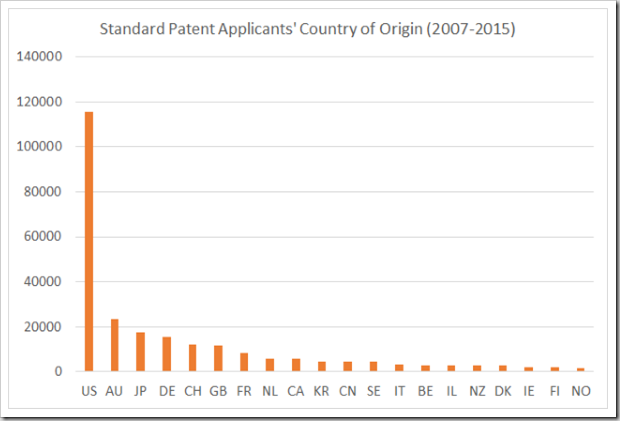

The chart below shows the total number of innovation patent applications filed during the 2007-2015 period by country of origin. Overwhelmingly, the biggest users of the system have been Australian residents.

The significance of this characteristic of the innovation patent system is perhaps best appreciated through a comparison with the equivalent statistics for standard patent application filings (including PCT national phase entries occurring during the relevant period), as shown in the following chart. In this case, it is US residents that are just as dominant as Australians are in the innovation patent data. It is also worth noting that, although Australians filed just 10%-15% of all standard patent applications over the 2007-2015 period, domestic applicants are nonetheless the second biggest users of the Australian patent system. Given that it is a very big world out there, and Australia is not an especially populous country, this is not a bad result and one that seems often to be overlooked when considering the extent of use of the system by Australian residents.

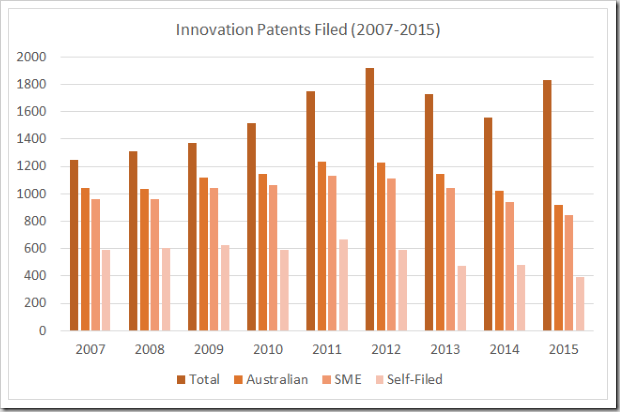

The chart below shows, for each year in the range:

- the total number of innovation patents filed;

- the number of these that were filed by Australian applicants;

- the number of these Australian filings that were made by SMEs (including individuals); and

- the number of the SME applications that were self-filed.

Clearly, the vast majority of domestic applications are individuals and SMEs – precisely the ‘target market’ of the innovation patent as it was originally conceived. Too many of these, however, a self-filers. As I have argued recently, there is very little value in the majority of self-filed applications, and thus these largely represent a dead-weight loss within the system. In my view, inexperienced self-filers should be actively discouraged, and their activities should be excluded from any analysis of the performance of the patent system.

As confirmation of this view, the chart below shows the corresponding annual numbers of innovation patents that went on to be examined and certified. As I have previously noted, innovation patent holders represented by patent attorneys request certification in 34% of cases, compared with only 16% of self-filers. SMEs again make up the vast majority of Australian patent-holders that go on to obtain certification, however the self-filers clearly perform extremely poorly in those cases where they do request examination, with very few of their patents being successfully certified.

Chinese Filers

The appearance of a significant number of Chinese entities in the top 30 innovation patent filers (but not among the certifiers) might come as a surprise. I have previously speculated that this behaviour has been induced by Chinese government subsidies that are handed out to companies that obtain foreign patents. One issue with the innovation patent is that the status of a granted innovation patent (that has not been substantively examined) is indistinguishable from that of a standard patent (that has) to anybody insufficiently familiar with the system. Thus obtaining an innovation patent grant is a low-cost approach to getting the evidence needed to receive a Chinese government payout.The chart below shows the number of innovation patents filed annually by Chinese applicants between 2007 and 2015. While there was a slow-down in 2013 and 2014, the Chinese ‘junk’ filers were back in force in 2015.

Agents Acting for Chinese Applicants

Clearly the filing of innovation patents for the purpose of obtaining government handouts is an abuse of the system in which no self-respecting patent attorney would knowingly involve themselves, right? To be clear, it is obviously legal, and if instructions to file an innovation patent are received from a Chinese client, in good faith, by an Australian attorney, then that attorney would generally have an obligation to act on those instructions in the interests of that client.An interesting question, however, is whether there are Australian attorney firms using Chinese subsidies for innovation patents as a marketing tactic to encourage this behaviour, and secure additional revenue and profits? I am not going to attempt to answer that question, because I really do not know anything about the international marketing strategies of most Australian firms. I simply present the data below for completeness. You may wish to compare these numbers with the overall market share of Australia’s top attorney firms that I published recently, and make your own suppositions.

The first table shows the top 10 firms for the filing of innovation patents on behalf of Chinese applicants, while the second shows a complete, unabridged list for all of the Chinese-originating innovation patents to have been certified between 2007 and 2015. The conclusion – however these firms came about their Chinese clients, only a handful appear to be serious about their ownership of enforceable Australian innovation patents.

Agents Filing for Chinese Applicants, 2007-2015

Rank

|

Agent Name

|

No.

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ADMIRAL SERVICES | 448 |

| 2 | SHELSTON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY | 113 |

| 3 | WRAYS | 90 |

| 4 | INTELLEPRO | 55 |

| 5 | SAKEI INTL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AGENCY FIRM | 40 |

| 6 | MADDERNS | 37 |

| 7 | DAVIES COLLISON CAVE | 34 |

| 8 | APT | 27 |

| 9 | PHILLIPS ORMONDE FITZPATRICK | 26 |

| 10 | PIPERS | 24 |

Agents Certifying for Chinese Applicants, 2007-2015

Rank

|

Agent Name

|

No.

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | DAVIES COLLISON CAVE | 16 |

| 2 | CULLENS | 6 |

| 3 | WATERMARK | 3 |

| 4 | MADDERNS | 2 |

| 5 | INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY STRATEGIES | 1 |

| 6 | JAMES WELLS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY | 1 |

| 7 | ACACIA LAW | 1 |

| 8 | MINTER ELLISON | 1 |

| 9 | MJ SERVICE ASSOCIATES | 1 |

| 10 | PHILLIPS ORMONDE FITZPATRICK | 1 |

| 11 | SHELSTON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY | 1 |

| 12 | SMOORENBURG | 1 |

| 13 | APT | 1 |

Conclusion – The Innovation Patent is Not Dead Yet...

...though it is not at all well, and its custodians seem as though they would be quite happy to whop it over the head and throw it in the cart rather than be inconvenienced by it any longer. This is despite the fact that it has served, and is clearly continuing to serve, the requirements of its target constituency, i.e. Australian SMEs.I have previously set out, in handy three-word slogans, my top five list of reforms to improve the innovation patent system, before going to the extreme of total abolition because, once gone, we will never get it back – nor, presumably, any other second-tier patent right. These are:

- Raise the Step;

- Limit the Damages;

- Reduce the Term;

- Stop the Injunctions; and

- Force the Examination.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment