The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has concluded that recent decisions of the US Supreme Court relating to patents for genes and for diagnostic methods mean that mixtures of ‘naturally-occurring materials’ are not patent-eligible – at least, not unless one or more of the components has been ‘changed’ in some way from its natural state.

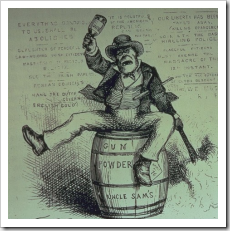

The US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has concluded that recent decisions of the US Supreme Court relating to patents for genes and for diagnostic methods mean that mixtures of ‘naturally-occurring materials’ are not patent-eligible – at least, not unless one or more of the components has been ‘changed’ in some way from its natural state.The USPTO has published an extensive (93-slide) presentation used for examiner training [PDF, 972KB] on the Supreme Court’s interpretation of section 101 of the US patent statute in Mayo Collaborative Services v Prometheus Laboratories, Inc. (2012) and Ass’n for Molecular Pathology v Myriad Genetics, Inc. (2013). In an example to be found on slide no. 55, examiners are told that ‘gunpowder’ would not be eligible for patenting (even if it was not already known) because as ‘a mixture of three naturally occurring materials: potassium nitrate, sulfur and charcoal’ it is ‘not markedly different’ from naturally-occurring materials, ‘because none of the components have been changed.’

This will no doubt come as a surprise to many people, who would not have held any real doubts that gunpowder was ‘invented’ by the Chinese, around the 9th century C.E. Indeed, as the quite well-researched Wikipedia entry on the History of Gunpowder explains, it took a few centuries, and a number of educational accidents, to refine the proportions of gunpowder’s constituent parts to produce maximum explosive effect.

While there is no question that effective gunpowder can be made by combining materials that occur in nature, the resulting combination is not (fortunately) naturally-occurring! There is, to my knowledge at least, nowhere in the natural world at which dangerously flammable reserves of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal can be found just lying around in wait of a serendipitous lightning strike! (Interestingly, however, there is evidence that 17 nuclear fission reactors once formed and operated naturally for around a million years in what is now Gabon, western Africa.)

Conventional wisdom would have it that, in the case of a combination like gunpowder, the prospective invention lies in bringing the components together to create something useful. If the combination is not previously known, and not obvious, then it should be patentable. Apparently, the USPTO no longer believes in this conventional wisdom!

Patent-Eligibility, Mayo and Myriad

Section 101 embodies the ‘threshold question’ of subject matter eligibility, i.e. whether the invention claimed is the kind of thing for which patents may be granted. In Australia, the analogous requirement is that a claimed invention must be for a ‘manner of manufacture’.In the Mayo decision, the Supreme Court held that a method for dosing a medication based on a patient’s metabolite levels after drug administration involved the application of a ‘law of nature’, and therefore was not patent-eligible. In the Myriad decision, the Court held that an isolated DNA molecule having a nucleotide sequence matching that of naturally occurring genes is ineligible because it is a ‘product of nature’.

The new USPTO guidelines for assessing subject-matter eligibility recognise that while section 101 identifies four categories of patentable subject matter – ‘any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter’ – the courts have in turn identified four exclusions, or ‘judicial exceptions’ – abstract ideas, laws of nature (or natural principles), natural phenomena, and natural products.

Contentious subject matter such as business methods and computer-implemented processes are considered for eligibility under the ‘abstract ideas’ exception. It is generally understood that mathematical formulae fall within this exclusion.

‘Laws of nature’ and ‘natural phenomena include natural principles and naturally-occurring relations or correlations, such as the ‘law’ of gravity, the disinfectant qualities of ultraviolet light and the relationship between blood glucose levels and diabetes (slide 20 of the USPTO presentation).

So What’s New in the USPTO Guidelines?

The new exclusion being applied by the USPTO in the wake of the Myriad case are those relating to ‘natural products’. According to slide 26, ‘eligibility requires more that “the hand of man”’. A ‘claimed product must be both non-naturally occurring, and markedly different from naturally occurring products.’The requirement for a marked (or ‘significant’) difference between the natural product and the claimed product is not new. In the 1948 case of Funk Brothers Seed Co. v Kalo Inoculant Co., 333 US 127, the Supreme Court found that claims directed to particular mixtures of bacteria, intended for application to leguminous plants, were not patent-eligible. The bacteria were naturally occurring, but different plants benefited from the presence of different bacteria, while other bacteria would inhibit the beneficial effects.

What Funk Brothers had found and patented was that certain combinations and strains of bacteria could be effective for a range of different plants, while avoiding the inhibiting effect that would normally be expected from the combination.

However, the Court determined that the qualities of the bacteria were naturally-occurring, and that the aggregation of selected strains of bacteria by Funk Brothers was a patent-ineligible application of a natural principle – albeit a principle that had not previously been known. The Court explained that:

The application of this newly discovered natural principle to the problem of packaging of inoculants may well have been an important commercial advance. But once nature's secret of the noninhibitive quality of certain strains of the species of Rhizobium was discovered, the state of the art made the production of a mixed inoculant a simple step. Even though it may have been the product of skill, it certainly was not the product of invention.

Funk Brothers – Ineligible, or Obvious?

The Funk Brothers case was decided under the previous US patent law, which did not make a clear distinction between ‘eligibility’ and ‘invention’ (i.e. what we would now regard as the requirement for nonobviousness under section 103). As can be seen in the above passage, it is not clear whether the Court was concerned that the claimed invention was too obvious to justify a patent or that when the discovery of a natural principle is applied in a trivial manner, then the subject matter is not patent-eligible.However, while the legal principles espoused in Funk Brothers have generally been approached with caution, the Supreme Court seems subsequently to have treated it as having been decided on eligibility rather than obviousness.

A later case, Diamond v Chakrabarty, 447 US 303 (1980), concerned a genetically-modified bacterium. By a slim majority (5-4), the Supreme Court held in Chakrabarty that a ‘live, human-made organism’ is patent-eligible, because it is ‘markedly different’ from the naturally-occurring organism from which it has been derived.

Myriad – A ‘Perfect Storm’ of Ineligibility?

In Myriad this older Supreme Court law has combined to create what the USPTO regards as the new rules for patent-eligibility in relation to naturally-occurring materials. As explained on slide 28 of the training package:- Myriad relies on Chakrabarty and serves as a reminder that Chakrabarty’s markedly different criterion is the eligibility test across all technologies for product claims reciting natural products

- Myriad explains that Funk Brothers’ combination of bacteria was not eligible because the patentee ‘did not alter the bacteria in any way’

Conclusion – The USPTO Must Have This Wrong!

In my opinion, what the USPTO is teaching its examiners simply cannot be right.It is a fundamental principle of the interpretation of patent claims that a claim must be considered as a whole. It may be that each individual element of a combination claim is well-known, however if the combination is novel then the claim is potentially patentable.

This does not mean that any simple, but previously undisclosed, combination of known components will automatically be eligible for patent protection. If each component of the combination merely performs its known function, with nothing new arising from an interaction between the parts, then what you have is what the Australian courts have called a ‘collocation’. Mere collocations are not patent-eligible. A new working relationship between parts is required for a combination of known components to be patent-eligible. I note that this is one way to understand the outcome in Funk Brothers.

But when potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal are brought together in suitable proportions, they unquestionably interact in ways that are not known in the natural world!

Of course, they only do so because they are following the ‘laws’ of chemistry, which are themselves the aggregate effect of the more fundamental ‘laws’ of physics. But even a mechanical device, such as a motor, operates by following the laws of physics once the constituent rotors, axles, bearings, gears etc have been brought together in a suitable arrangement by human design. The mere fact that inventions follow the laws of nature does not disqualify them from patentability, otherwise nothing would be patent-eligible!

I understand that the USPTO is inviting public comment on its guidelines, via email to myriad-mayo_2014@uspto.gov. I expect it will receive much strongly-worded feedback!

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

11 comments:

In Chakrabarty the Supreme Court noted that the combined bacteria of Funk Brothers had the same structure, function, and utility, and mentioned the lack of new function/utility several times, so why did the USPTO focus on structure? I really don't think the Supreme Court in Myriad meant to do away with patents on newly discovered drugs or new combinations that do have new functions and uses. The question now is how long will it take to get these Guidelines withdrawn or overturned, and how much damage will be done in the meantime?

Thanks for your comment, Courtenay.

I find it interesting that both Australian and US patent law continue to experience a hangover from prior legislation in which there was no express distinction drawn between eligibility and non-obviousness. Coincidentally (I assume) both countries introduced an explicit non-obviousness (or inventive step) requirement with statutes enacted in 1952.

It does not help that the word 'invention' can be interpreted either as the subject matter itself, or as the act of conception.

Fortunately, the Australian High Court has, in recent years, been at pains to emphasise the importance of treating each of the criteria for patentability separately, and to discourage the notion that there is a legitimate overlap between subject matter and inventive step. It is not apparent to me that the US Supreme Court has demonstrated the same clarity of thought.

One thing some of us are wondering down-under is whether the USPTO interpretation of the Myriad decision, if correct, places the United States in breach of its obligations under various international agreements, such as Chapter 17 of the Australia-US Free Trade Agreement (AUSFTA). The US is generally very quick to criticise trading partners for any perceived weaking of IP protections!

Article 17.9(1) of the AUSFTA clearly states that '[e]ach Party shall make patents available for any invention, whether a product or process, in all fields of technology, provided that the invention is new, involves an inventive step, and is capable of industrial application. The Parties confirm that patents shall be available for any new uses or methods of using a known product.'

Article 17.9(2) provides that each Party may only exclude from patentability '(a) inventions, the prevention within their territory of the commercial exploitation of which is necessary to protect ordre public or morality, including to protect human, animal, or plant life or health or to avoid serious prejudice to the environment, provided that such exclusion is not made merely because the exploitation is prohibited by law; and (b) diagnostic, therapeutic, and surgical methods for the treatment of humans and animals.'

Excluding genomic DNA is no doubt arguably covered under (a), while the outcome in Mayo clearly falls within (b). But if new and useful combinations, uses and methods of using natural products are generally excluded under 35 USC 101, as the USPTO has concluded, it is difficult to see how this is consistent with the obligations of the US under Article 17.9(1) of the AUSFTA.

Nice article. Your

guidance is so helpful.. we are also from pps

registration

I don't think the USPTO is really saying that gunpowder couldn't be patented. They're using it as an example of how something that is not otherwise eligible (the mere collocation of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal) can be made eligible by limiting the claim in the way the first part of the example on slide 54 does (by limiting it to gunpowder used in a kind of firework).

So if I invented gunpowder today I couldn't get a patent giving me a monopoly on all possible mixtures of those three ingredients created or used for any purpose whatsoever, but I might be able to get a patent on the use of the mixture as an explosive. That seems unobjectionable to me.

The U.S. Supreme Court rarely enhances the clarity of the U.S. patent laws -- we will see what they do after today in CLS Bank! There is concern (hope?) that the Guidelines will be seen as violating international trade agreements. Would you mind if I used your comments on a PharmaPatents blog post, or would you like to write a guest post with the Australian perspective?

Hi Robert,

As I read it, slide 55 is stating that the term 'gunpowder' appearing in a claim cannot contribute to patent-eligibility, because it encompasses the ineligible combination of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal, in which none of those components has been modified in any way from its 'natural state'.

By definition, however, the combination must still satisfy the properties inherent in the use of the term 'gunpowder', so I do not understand this to be a reference to 'all possible mixtures of those three ingredients created or used for any purpose whatsoever'.

The slide goes on to distinguish the 'broad' term gunpowder from a specific embodiment in which the components have been altered so as to be 'structurally different from what exists in nature' (namely, a composition in which sodium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal are mixed and then granulated, and then the granulated particles are coated with a thin layer of graphite).

As Courtenay points out in her earlier comment, this focus on structure seems inappropriate. If a new and non-naturally-occurring combination of natural components has a new function or use, it is difficult to see why it should not be patentable even if there have been no structural modifications made to the naturally-existing constituents.

The guidance suggests that a claim of the form 'an explosive comprising potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal in [specified proportions or ranges thereof]' would not be patent-eligible unless some structural change has been made to one or more of the components, and incorporated into the claim.

Mark,

Slide 55 has to be read in its context as a note clarifying the example in slide 54, which is itself based on an example in the separate guidance material. The point being made is that a claim like "a mixture of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal" that does not mention any function or use wouldn't be eligible because it is simply a combination of things existing in nature, but a claim like "an explosive containing a mixture of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal" might be because it is limited similarly to the way described on slide 54 and in example C in the guidance. The kind of structural change described in "Type II" on slide 55 is just another, different way to get eligibility.

I think slide 54 itself supports Mark's position. It specifically states that "the calcium chloride and gunpowder are not markedly different from what occurs in nature."

The context of slide 55 is that it is explaining why 'gunpowder' itself is not patent eligible - gunpowder can include "a mixture of potassium nitrate, sulphur and charcoal."

The invetiable conclusion is that (under these guidelines) you couldn't get a patent on the use of the mixture as an explosive.

Robert, I sincerely hope you are correct. However the consensus among many of my colleagues, and from much of the feedback I have received here, via email and on Twitter, is that the USPTO should not be given the benefit of the doubt. It has the opportunity to clarify its guidance and, if it intends to continue to grant patents for mixtures of naturally-occurring materials, in appropriate circumstances, then it should say so!

I agree. My reading of slide 54 is that what is said to grant the firework patent-eligibility is the physical scructure of the cardboard body with its first and second compartments configured to contain the unpatentable mixtures of naturally-occurring materials.

In my view, the USPTO Guidelines are an accurate reflection of the USSC jurisprudence, and it

is the USPTO itself which is wrong. See my article The Rule Against Abstract Claims: A Critical

Perspective on US Jurisprudence, (2011) 27 Can IP Rev 3 available on SSRN

abstract_id=1782747. See also my IPKat posts on Mayo, 21 Mar 2012; Myriad 17 June 2013;

and CLS Bank 14 May 2013.

Post a Comment