A biological medicine, or biologic, is a medicine that contains one or more active substances made by a biological process or derived from a biological source. Compared to conventional pharmaceuticals, which are made by chemical synthesis using different organic and/or inorganic compounds, biologics are generally much larger molecules that are derived from the living cells of micro-organisms or animals by utilizing the metabolic processes of the organisms themselves. In many cases, cells are genetically engineered, using recombinant DNA technology, to co-opt their expression capabilities and turn them into tiny ‘factories’ for producing the desired biologic molecules. The first such substance to be approved for therapeutic use was synthetic ‘human’ insulin, developed by Genentech and first marketed by Ely Lilly in 1982. Since then, biologics have become increasingly important, and hundreds of biologic medicines are now in use, including therapeutic proteins, DNA vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and fusion proteins.

A biological medicine, or biologic, is a medicine that contains one or more active substances made by a biological process or derived from a biological source. Compared to conventional pharmaceuticals, which are made by chemical synthesis using different organic and/or inorganic compounds, biologics are generally much larger molecules that are derived from the living cells of micro-organisms or animals by utilizing the metabolic processes of the organisms themselves. In many cases, cells are genetically engineered, using recombinant DNA technology, to co-opt their expression capabilities and turn them into tiny ‘factories’ for producing the desired biologic molecules. The first such substance to be approved for therapeutic use was synthetic ‘human’ insulin, developed by Genentech and first marketed by Ely Lilly in 1982. Since then, biologics have become increasingly important, and hundreds of biologic medicines are now in use, including therapeutic proteins, DNA vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, and fusion proteins. The chemical structures of traditional ‘small molecule’ pharmaceuticals are usually well-defined. Biologics, on the other hand, are often difficult, and sometimes impossible, to characterise structurally due to their size and complexity. In many cases, some components of a finished biologic may be unknown. Protecting biologics with patents can therefore be challenging, given the potential difficulty in claiming the active biologic molecule in terms that are sufficiently precise to meet legal requirements for the invention to be clearly defined, while also being broad enough to encompass variations that may have the same therapeutic properties, and satisfying the tests for novelty, inventive step and subject-matter eligibility.

The complexity of biologics also means that they are more difficult to produce than small molecule pharmaceuticals. Minor differences in the production process, raw materials, temperature, pH, or cell line can result in a significant alteration in a medicine’s quality, efficacy, or safety. While this creates challenges in manufacturing and quality control, it also creates opportunities for the protection of intellectual property, by securing patents on methods of producing biologic medicines either in place of, or in addition to, trying to claim the active molecules themselves in some form.

Process claims are all very well if the patentee can established that a suspected infringer is using the patented method of production. But what happens when the suspect company keeps its manufacturing processes secret, as indeed is most commonly the case? Well, then the patentee may need to convince a judge to issue an order for preliminary discovery, compelling the accused infringer to disclose relevant information about its processes.

This is exactly what Pfizer recently sought to do in preparation for possible patent litigation against Samsung Bioepis AU (‘SBA’) in relation to Pfizer’s product ENBREL (active ingredient etanercept), which is a biological medicine used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Unfortunately for Pfizer, Justice Stephen Burley has denied its application for discovery, ruling its evidence insufficient to establish a ‘reasonable belief’, as opposed to a ‘mere suspicion’, that SBA is infringing its patents relating to a process for producing etanercept: Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals v Samsung Bioepis AU Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 285.

Last month I presented

Last month I presented  Under

Under  According to

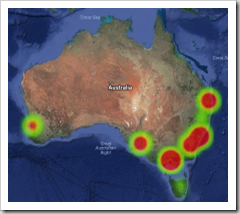

According to  In an eight year period – one full innovation patent lifecycle – between 2007 and 2015, Australian residents were overwhelmingly the biggest users of the second-tier innovation patent system, filing over 10,000 innovation patent applications. The next most frequent filers were the Chinese, with just 1500 applications, followed by US applicants with less than 1000. Over 90% of the Australian applicants were individuals or small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs – businesses with fewer than 200 employees), i.e. the exact people the innovation patent system was intended to benefit when it was established by the Howard Government in 2001. Over the same period, Australian residents filed just over 23,000 standard patent applications, a very distant second to US residents who were responsible for 115,000 applications.

In an eight year period – one full innovation patent lifecycle – between 2007 and 2015, Australian residents were overwhelmingly the biggest users of the second-tier innovation patent system, filing over 10,000 innovation patent applications. The next most frequent filers were the Chinese, with just 1500 applications, followed by US applicants with less than 1000. Over 90% of the Australian applicants were individuals or small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs – businesses with fewer than 200 employees), i.e. the exact people the innovation patent system was intended to benefit when it was established by the Howard Government in 2001. Over the same period, Australian residents filed just over 23,000 standard patent applications, a very distant second to US residents who were responsible for 115,000 applications.