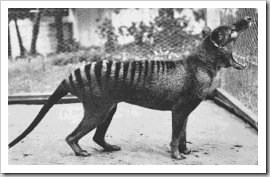

The photograph accompanying this article is of ‘Benjamin’, the last known thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), which died in captivity in the Hobart zoo, most likely as a result of neglect, on 7 September 1936. Benjamin had been captured in 1933, three years after the last thylacine known to have been shot in the wild was killed by a farmer. Indeed, a major contributor to the thylacine’s extinction was its inconvenience to farmers. As the largest carnivorous marsupial of modern times, the thylacine was blamed for the slaughter of livestock, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult animals and ten shillings for pups – which was a lot of money at the time.

The photograph accompanying this article is of ‘Benjamin’, the last known thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), which died in captivity in the Hobart zoo, most likely as a result of neglect, on 7 September 1936. Benjamin had been captured in 1933, three years after the last thylacine known to have been shot in the wild was killed by a farmer. Indeed, a major contributor to the thylacine’s extinction was its inconvenience to farmers. As the largest carnivorous marsupial of modern times, the thylacine was blamed for the slaughter of livestock, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult animals and ten shillings for pups – which was a lot of money at the time.The innovation patent is another unique Australian creature that is about to become extinct at the hand of government policy. Unfortunately for the innovation patent, it has become a great inconvenience to economists, within IP Australia and at the Productivity Commission, who believe that the system, and in particular the low threshold for the innovative step, contributes to low value patents, which they blame for the imposition of unacceptable costs on the community. IP Australia has now published draft legislation and rules (the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 1 and Other Measures) Bill and Regulations 2017) including measures to implement aspects of the Government’s response to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into Australia’s Intellectual Property arrangements. These measures include the abolition of the innovation patent which will, if the draft legislation becomes law in its current form, go out like the thylacine, not with a bang but a whimper, dwindling slowly away over eight years after the last shot has been fired against it.

Of course I am aware that the extinction of an entire species is a tragedy of criminal proportions, and that comparison with the mere repeal of a second-tier patent system is hyperbole of the highest order. But I am using this rhetorical device to highlight the analogous manner in which government policy is driven in each case by a single perspective on the problem at hand. Both the thylacine bounty and the abolition of the innovation patent are the result of governments acting on input provided by particular interest groups, i.e. farmers and economists respectively. Just as the 19th century was a different time, when there would have been little public interest in, or opposition to, the culling of a unique native animal to protect farmers’ livelihoods (and the food supply), there is today very little interest from the broader community in challenging economists’ views on what is best for Australia’s innovation and intellectual property systems.

Economic modelling has become one of the primary drivers of so-called evidence-based policy-making, despite the fact that very few people (including most, if not all, politicians) could claim to understand the economists’ models, assumptions, or the statistical methods used to produce their ‘evidence’. In fact, economic models rarely make reliable predictions, even when they fit past data well. Just this past week, the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia has conceded that the Bank can only ever predict even the most basic economic indicators within a wide margin of error and that, ‘not surprisingly, forecast misses are more common than not’. If the country’s top central bankers cannot predict headline figures like economic output and inflation with any precision, what prospects do economists have of predicting the long-term impact of different options within the Australian patent system on national innovation and productivity?

Sadly, we will never know if there was a solution better than ‘termination with extreme prejudice’ to the problems posed by either the thylacine or the innovation patent. But, once we accept that the innovation patent must and will die, IP Australia’s current proposal seems like a soft option. I say that if we are going to abolish the innovation patent, it should be done as swiftly and decisively as possible!

A few weeks back

A few weeks back  It is the function of a patent claim to define the scope of the invention protected by the patent. Infringement occurs when an accused system, article, or process is covered by the particular terminology used in a patent claim. Many inventions are combinations, e.g. a system, article, or process made up of two or more elements, components, or steps that work together to provide some new and useful function or result. Claims directed to such inventions must therefore recite the relevant combination.

It is the function of a patent claim to define the scope of the invention protected by the patent. Infringement occurs when an accused system, article, or process is covered by the particular terminology used in a patent claim. Many inventions are combinations, e.g. a system, article, or process made up of two or more elements, components, or steps that work together to provide some new and useful function or result. Claims directed to such inventions must therefore recite the relevant combination. Australia has a pre-grant patent opposition system, meaning that an opportunity is provided after a standard patent application has been approved by an examiner, but before a patent is actually granted, for third parties to raise objections. Specifically, once an application has be accepted for grant, the accepted specification is published and there is then a three-month period during which anybody who believes that the granted patent would be invalid (wholly, or in-part) may file a notice of opposition. The filing of such a notice commences the formal opposition procedures defined in the Australian

Australia has a pre-grant patent opposition system, meaning that an opportunity is provided after a standard patent application has been approved by an examiner, but before a patent is actually granted, for third parties to raise objections. Specifically, once an application has be accepted for grant, the accepted specification is published and there is then a three-month period during which anybody who believes that the granted patent would be invalid (wholly, or in-part) may file a notice of opposition. The filing of such a notice commences the formal opposition procedures defined in the Australian