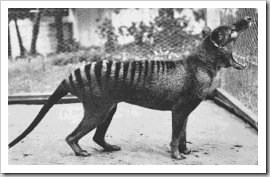

The photograph accompanying this article is of ‘Benjamin’, the last known thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), which died in captivity in the Hobart zoo, most likely as a result of neglect, on 7 September 1936. Benjamin had been captured in 1933, three years after the last thylacine known to have been shot in the wild was killed by a farmer. Indeed, a major contributor to the thylacine’s extinction was its inconvenience to farmers. As the largest carnivorous marsupial of modern times, the thylacine was blamed for the slaughter of livestock, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult animals and ten shillings for pups – which was a lot of money at the time.

The photograph accompanying this article is of ‘Benjamin’, the last known thylacine (commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger), which died in captivity in the Hobart zoo, most likely as a result of neglect, on 7 September 1936. Benjamin had been captured in 1933, three years after the last thylacine known to have been shot in the wild was killed by a farmer. Indeed, a major contributor to the thylacine’s extinction was its inconvenience to farmers. As the largest carnivorous marsupial of modern times, the thylacine was blamed for the slaughter of livestock, and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 per head for dead adult animals and ten shillings for pups – which was a lot of money at the time.The innovation patent is another unique Australian creature that is about to become extinct at the hand of government policy. Unfortunately for the innovation patent, it has become a great inconvenience to economists, within IP Australia and at the Productivity Commission, who believe that the system, and in particular the low threshold for the innovative step, contributes to low value patents, which they blame for the imposition of unacceptable costs on the community. IP Australia has now published draft legislation and rules (the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Productivity Commission Response Part 1 and Other Measures) Bill and Regulations 2017) including measures to implement aspects of the Government’s response to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into Australia’s Intellectual Property arrangements. These measures include the abolition of the innovation patent which will, if the draft legislation becomes law in its current form, go out like the thylacine, not with a bang but a whimper, dwindling slowly away over eight years after the last shot has been fired against it.

Of course I am aware that the extinction of an entire species is a tragedy of criminal proportions, and that comparison with the mere repeal of a second-tier patent system is hyperbole of the highest order. But I am using this rhetorical device to highlight the analogous manner in which government policy is driven in each case by a single perspective on the problem at hand. Both the thylacine bounty and the abolition of the innovation patent are the result of governments acting on input provided by particular interest groups, i.e. farmers and economists respectively. Just as the 19th century was a different time, when there would have been little public interest in, or opposition to, the culling of a unique native animal to protect farmers’ livelihoods (and the food supply), there is today very little interest from the broader community in challenging economists’ views on what is best for Australia’s innovation and intellectual property systems.

Economic modelling has become one of the primary drivers of so-called evidence-based policy-making, despite the fact that very few people (including most, if not all, politicians) could claim to understand the economists’ models, assumptions, or the statistical methods used to produce their ‘evidence’. In fact, economic models rarely make reliable predictions, even when they fit past data well. Just this past week, the deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia has conceded that the Bank can only ever predict even the most basic economic indicators within a wide margin of error and that, ‘not surprisingly, forecast misses are more common than not’. If the country’s top central bankers cannot predict headline figures like economic output and inflation with any precision, what prospects do economists have of predicting the long-term impact of different options within the Australian patent system on national innovation and productivity?

Sadly, we will never know if there was a solution better than ‘termination with extreme prejudice’ to the problems posed by either the thylacine or the innovation patent. But, once we accept that the innovation patent must and will die, IP Australia’s current proposal seems like a soft option. I say that if we are going to abolish the innovation patent, it should be done as swiftly and decisively as possible!

Draft Proposal

Implementation of the proposed ‘phasing out’ of the innovation patent in the draft legislation is straightforward. The Patents Act 1990 and the Patents Regulations 1991 would be amended such that:- no innovation patent could be validly granted on an application having a effective filing date on or after the day on which the amendments come into force; and

- no innovation patent claim could be validly certified having a priority date on or after that day.

Thus, under the proposed phase-out there will not only be some existing innovation patents still in effect for up to eight years (i.e. the maximum innovation patent term) after the Act and Regulations are amended, but there will also still be new innovation patent granted throughout this period.

Does the Proposed Phase-Out Make Sense?

To explain why I consider the proposed legislation to be a soft option, it is worth reiterating some of the most significant problems with the innovation patent system.- The ‘innovative step’ standard is too low. This means that ‘inventions’ that fall far short of the usual ‘inventive step’ threshold may be protected by innovation patents which provide patentees with the same rights and remedies (i.e. injunctions and monetary compensation) as a standard patent. Alternatively, valid innovation patent claims may be broader in scope than their standard patent counterparts.

- Certification of innovation patents is optional. An innovation patent is granted without substantive examination, but is only enforceable after it has been examined and certified. This leads to uncertainty for competitors, because the validity of a granted, but uncertified, innovation patent is unknown. Additionally, the claims of an innovation patent may be amended in the course of examination, which is a source of further uncertainty.

- Divisional innovation patents are commonly used for strategic purposes. An applicant with a pending standard application can quickly obtain and certify a divisional innovation patent to target potentially infringing activities of a competitor. The innovation patent may be of different scope to its parent and, due to the low ‘innovative step’ threshold, may be almost impossible for an accused infringer to invalidate.

So, under the proposed phase-out, only applicants that have already filed for standard patent protection prior to amendment of the Act and Regulations will be able to obtain new innovation patents, either by division or conversion. Meanwhile, Australian SMEs that develop new lower-level innovations falling below the ‘inventive step’ threshold, and not protectable via a registered design, will no longer have any means of protection available.

During the phasing-out period, therefore (eight years, remember), we will continue to have an innovation patent system with all of the existing problems, and none of the existing benefits.

That makes no sense to me.

Seriously, Just Rip Off the Band-Aid!

So here is what I would do.First, I would bring the creation of all new innovation patents to a dead halt. It would not be possible to file any new innovation patent, including divisionals, on or after the date of commencement of the amending legislation. It would, of course, still take up to eight years for the last of the existing innovation patents to expire. However, the uncertainty associated with the possibility of divisional innovation patents being filed from any of the tens of thousands of pending standard applications (there are, according to an AusPat search, 61,204 such applications at the time of writing) would be eliminated.

Second, I would ‘sunset’ requests for examination and certification of existing innovation patents. I can see no reason why owners of legacy innovation patents should be permitted to leave them uncertified indefinitely when the system is being phased out. Any innovation patent for which no request for examination has been filed by the end of two years following amendment of the Act and Regulations should automatically cease. Aside from anything else, this would help to address the possibility of a rush on applications for innovation patents shortly before the changes come into effect. It is one thing to file an application while you still can, just in case, but another altogether to go to the trouble and expense of having it examined in the absence of any specific need for an enforceable right. Indeed, since commencement of the innovation patent system in May 2001, up until the end of 2016 (according to IPGOD 2017 data), examination was requested on only 22.5% of all innovation patents, resulting in just 16% being certified.

My proposal would thus result in a massive reduction in the number of innovation patents, and the elimination of all associated uncertainty, within two years of the commencement of the amendments to the Act and Regulations. If we must get rid of the innovation patent system, we should do it properly, and do it quickly. The alternative is likely to be more harmful to Australian SMEs – the supposed beneficiaries of the innovation patent – than just leaving the system alone.

Impact on ‘Existing Rights’

The draft Explanatory Memorandum explains the proposed mechanism for phasing out the innovation patent as follows:Abolishing the innovation patent system is not intended to affect existing rights. The system will continue to operate for innovation patents that were filed before these amendments commence. In addition, existing rights to file divisional applications and convert a standard patent application to an innovation patent application will be maintained for any patent or application that was filed prior to the commencement date of these amendments.

Of course any amendment to the law should not affect existing rights, or have any retroactive effect. But I can see no reason why the ‘existing right’ to file divisional innovation patent applications, or to convert standard applications to innovation patents, should be maintained. Nobody files a standard patent application with the intention or expectation that they will be filing divisional innovation patents, or converting to an innovation patent, at some unspecified future time. Indeed, around 90% of all applicants for Australian standard patents are foreign residents, many of whom would be unaware of the existence of the innovation patent system. In any case, existing applicants will have adequate notice, prior to the commencement of the amending legislation, that the innovation patent system is being abolished, and will have the opportunity to file divisional applications or to convert their existing applications, should they have a positive intention to do so.

There is precedent in Australia for such an approach. When the Raising the Bar reforms commenced on 15 April 2013, it might have been argued that any applicant with a filing date (or even, perhaps, a priority date) earlier than this had an ‘existing right’ to have their application examined and granted under the lower standards of the prior law. And, indeed, they did have such a right. However, under the transitional provisions relating to the amendments, in order to exercise this right they needed to have their application filed, and make a request for examination, before the commencement date of the amended law. There would be no difference, in principle, in cutting off all new innovation patent filings.

Conclusion – If We’re Gonna Do It, Let’s Do It Right!

In the past, I have defended the innovation patent. I have suggested that, rather than going straight for abolition, the system could perhaps have been improved to address its problems. And I have argued that, despite the conclusions from the economists’ modelling, the innovation patent system has substantially served its intended market of Australian SMEs. More recently, however, I have thrown in the towel and accepted that the defences of the system are weak in the face of the forces that have amassed against it.So if we must abolish the innovation patent system, we should do it quickly, we should do it decisively, and we should do it in a way that best serves the interests of the Australian community generally, and Australian SMEs in particular. And allowing existing standard patent applicants – most of whom are foreign residents – continuing access to innovation patents, when innovative Australians can no longer take advantage of the system for their new inventions, simply fails this test.

Frankly, I am surprised to see IP Australia showing such weakness on this issue. It was a very different story in the lead-up to the Raising the Bar reforms, where the originally-proposed transitional provisions would have had the higher standards of patentability apply, effectively retrospectively, to any existing application for which a first examination report was yet to issue – something over which the applicant has limited control. IP Australia only walked-back this harsh proposal in the face of strong objections from the patent attorney profession and other stakeholders.

IP Australia is seeking feedback on the draft legislation, with written submissions due by 4 December 2017 via email to consultation@ipaustralia.gov.au. It is too late to argue against abolition of the innovation patent system, with IP Australia expressly stating that it is not looking for comments on the policy underpinning the amendments, which has already been agreed to by the Government – you will need to take that up with you local Member of Parliament, I guess. As for the implementation, however, if you agree with me, or even if you do not, I encourage you to make a submission.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment