A new research dataset released by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) reveals that since the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued its 2010 ruling in Bilski v Kappos, the rate at which US patent applications are rejected on subject-matter grounds (as compared with other grounds of rejection) has increased from 8% to 13%. (A hat-tip, by the way, to Dennis Crouch at the Patently-O blog for bringing this new dataset to my attention, and using it to compare rates of anticipation and obviousness rejections over the period covered by the data.)

A new research dataset released by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) reveals that since the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) issued its 2010 ruling in Bilski v Kappos, the rate at which US patent applications are rejected on subject-matter grounds (as compared with other grounds of rejection) has increased from 8% to 13%. (A hat-tip, by the way, to Dennis Crouch at the Patently-O blog for bringing this new dataset to my attention, and using it to compare rates of anticipation and obviousness rejections over the period covered by the data.)As interested followers of patent-eligibility (you know who you are) will be aware, during this period the Supreme Court has issued four opinions restricting the scope of patentable subject matter: Bilski v Kappos 130 S.Ct. 3218 (2010), relating to ‘pure’ business methods; Mayo v Prometheus 132 S.Ct. 1289 (2012), relating to diagnostic methods; AMP v Myriad 133 S.Ct. 2107 (2013), relating to isolated genetic materials; and Alice v CLS Bank 134 S.Ct. 2347 (2014), relating to computer-implemented business methods. Each of these decisions resulted, at least initially, in an increase in subject-matter rejections by the USPTO in the corresponding fields of endeavour. And while there have been subsequent declines in the rates of Bilski- and Myriad-based rejections, the signs are that rates of rejection based on Mayo and Alice are at least steady, and possibly increasing.

Notably, updates to USPTO examination guidance on subject matter eligibility in July 2015 and May 2016, which were regarded by many as providing much-needed clarification expected to reduce the rates of rejection, do not appear to have had any impact on overall subject-matter rejection rates, or on the rates in the specific fields most affected by Bilski, Alice, Myriad, and Mayo.

Overall, the SCOTUS impact since 2010 appears to have been an increase in the relative number of patent-ineligible inventions for which applications are filed at the USPTO, averaged across all fields of endeavour, of around 60%! Another, more pragmatic, way of looking at the data is to say that for every 100 applications filed, around five (i.e. one in 20) will now be rejected on subject-matter grounds, that would not have been rejected prior to June 2010. Of course, the retrospective effect of the Court’s determinations on eligibility means that patents previously granted are not saved by preceding the recent decisions, which is why there has also been carnage in the US Federal Courts.

This all creates additional uncertainty around the availability and value of patents in affected technology areas, to the detriment of investors, innovators, and the patent system itself.

The Office Actions Research Dataset

As explained on the USPTO’s Open Data Portal site, the Office Actions Research Dataset:Contains detailed information on 4.4 million Office actions mailed from 2008 through June 2017 for 2.2 million publicly viewable patent applications. The data are sourced from the text of Non-Final Rejection and Final Rejection Office actions issued by patent examiners to applicants during the patent examination process. The data files include information on grounds for rejection raised, the claims in question, and pertinent prior art.

While this could be taken to mean that the dataset includes all published Office Actions since 2008, that is not the case. In fact, the dataset corresponds with all published applications starting with application serial number 12/000,001, and it just happens that the first Office Action on any of these applications issued in early 2008.

By way of illustration, the chart below shows the total number of Office Actions in the dataset issued in each month from January 2009 to December 2016, which include at least one statutory rejection – i.e. subject matter ineligibility or statutory double patenting under 35 USC 101, anticipation (lack of novelty) under 35 USC 102, obviousness (lack of inventive step) under 35 USC 103, and written description or claims issues under 35 USC 112. To be clear, this data does not include allowances (which are not part of the data set), or Office Actions including only objections and/or non-statutory double patenting rejections (both of which are generally formalities that can be readily overcome).

The dataset is enriched by using a number of computational techniques to analyse the text of Office Actions to identify and summarise specific grounds of rejection. Since this process is somewhat dependent upon USPTO examiners complying consistently and comprehensively with recommended practices for the preparation of Office Actions, the resulting dataset is not perfect. Approximately 20% of all Office Actions in the dataset are tagged as showing some form of irregularity, although the proportion for which this actually affects the quality of key data would be somewhat lower. Headings and form paragraphs – which would be most important for reliably classifying subject-matter rejections – were identified in 84% of Office Actions, and additional analysis techniques would enable some classification of many of the remaining 16% of Office Actions.

Relevantly to my analysis here, the dataset includes indications, for each Office Action, as to whether a 101-rejection was raised, as well as whether or not the examiner explicitly cited Alice, Bilski, Mayo, and/or Myriad in a form paragraph.

All Subject-Matter Rejections

The chart below shows the monthly rate of subject-matter (i.e. ‘101’) rejections of applications within the dataset. I define the ‘rate’ as the fraction, or percentage, of all Office Actions that include at least one statutory rejection.

The data clearly exhibits an increase in 101-rejection rate (from around 8% to around 11%) following the Bilski decision in June 2010, followed by a gradual decline towards the historic rate prior to a larger step-increase (to around 13%) corresponding with the Alice decision in June 2014. Subsequently, no further net decline in 101-rejections is apparent.

The impact of Mayo (March 2012) and Myriad (June 2013) is not visible in the above chart, mainly because the number of applications relating to computer-implemented subject matter, including business methods, is much higher than the number relating to genetic technology and diagnostic methods. Any Mayo/Myriad effect is therefore swamped by the Alice/Bilski effect. Additionally, I have seen biotechnology cases in which Alice is cited, because it is the most recent decision and includes a summary of general principles applicable to all subject matter, whereas Mayo and Myriad are unlikely to be cited in software or business method cases.

Breakdown of Subject-Matter Rejections

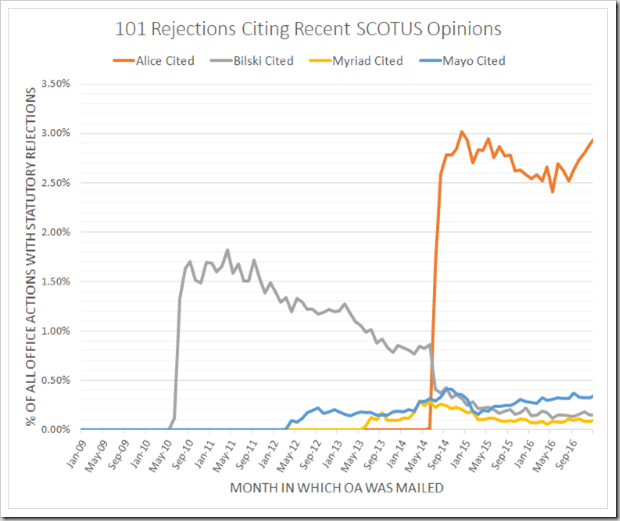

In order to better illustrate the relative impacts of Bilski, Myriad, Mayo and Alice, the chart below shows the citation rates of each of these cases in 101-rejections, as classified in the dataset. Again, ‘rates’ here are relative to the total number of Office Actions that include a statutory rejection.

Bilski and Myriad both resulted in a similar pattern of an initial rise in rejections, followed by a peak and steady decline. It is likely that there are two contributions to this effect, from applicants and examiners respectively. On the applicant side, I would expect that awareness of the relevant cases would result in some ‘hopeless’ applications being abandoned, while others would be amended (or initially filed) to include more-defensible claims in light of the Court’s reasoning. Additionally, examiners could be expected initially to err on the side of rejection, but over time to become more confident in applying the law to cases with allowable claims.

The effect of Mayo and Alice, however, has been quite different. Neither has shown any net decline as a basis for 101-rejections. Alice-based rejections showed some reduction following an initial steep rise, but more recently have returned to a similar rate to when the Court first issued its decision. Mayo-based rejections exhibited a temporary peak and decline around 2014-2015, but aside from this ‘blip’ have been increasing overall since the decision issued. These trends are disturbing, in that they suggest that little progress is being achieved in consistency and comprehension of the law as set out in either Mayo or Alice by examiners or applicants (or, more to the point, their attorneys). Clearly, applicants are continuing to put forward, and argue for, claims, while examiners are continuing to reject them at similar or increasing rates.

In this context, it is notable that none of the traces in the above chart exhibit any significant response to updates to USPTO examination guidance on subject matter eligibility that were published in July 2015 and May 2016. The purpose of this guidance is to assist examiners, and the purpose of publishing it is to inform applicants of the way in which the USPTO is applying the law in examination. This should result in improved understanding and consistency in decision-making by examiners and applicants. This should in turn cause a reduction in rejections, either because examiners and applicants are more able to agree on allowable subject matter, or because applicants elect to abandon applications that stand little chance of allowance under the guidance. Neither appears to have happened, which suggests that the guidance may not be as helpful as it is intended to be.

Biotechnology v Computer/Business Rejections

Broadly speaking, the Bilski/Alice and Myriad/Mayo decision-pairs are applicable to disparate fields of endeavour, i.e. computers/business methods and diagnostics and/or biotechnology respectively. It is apparent from the previous chart that Alice largely displaced Bilski as a basis for rejection. Myriad and Mayo seem to have been more complementary, although over time Mayo-based rejections have increased while Myriad-based rejections have declined.To illustrate the overall effect of the two pairs of decisions, the chart below shows the combined rates for each pair.

The chart confirms that subject-matter rejection in diagnostics and biotechnology continue to rise despite increasing applicant and examiner experience with applying the law. Furthermore, following what appears to have been a decline in Bilski/Alice-based rejections of computer-implemented and/or business method inventions, these have more recently risen back to post-Alice levels.

Conclusion – Is Eligibility Law a Complete Mess?

In my opinion, the most troubling thing about the data presented in this article is that rates of rejection based on Alice and Myriad do not appear to be in decline. Rejections based on Bilski and Mayo show the behaviour that I would logically expect, i.e. an initial increase, resulting from the immediate change in understanding of the law caused by the Court’s decision, followed by a decline, as examiners and applicants alike become more familiar with the law, and confident in applying it to their own cases.The fact that this is not happening with Alice and Myriad strongly suggests that the law set out in these decisions is largely unworkable, in the sense that different minds are unable to agree on what it means, or how to apply it in particular concrete cases. The issuance of a number of subsequent cases by the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (which seems to be just as confused and divided as everyone else), and the development of USPTO guidelines, do not appear to have had any positive impact on the situation.

And, as I pointed out in recent article, the situation does not appear to be any better in Australia.

In short, the law relating to subject-matter eligibility is a complete mess, at least in the US and Australia, with no signs of any significant improvement on the horizon. And if there is one thing that is bad for investment in innovation and the commercialisation of intellectual property, it is uncertainty. A patent system that contributes to uncertainty is thus one that is destined to fail in its primary objective of incentivising innovation.

Links:

- The USPTO Patent Application Office Actions Research Dataset;

- Paper describing the dataset: USPTO Economic Working Paper No. 2017-10, USPTO Patent Prosecution Research Data: Unlocking Office Action Traits [PDF, 875kB]

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment