This is a guest contribution from Kelvin Tran of Litimetrics. Further details about the author can be found at the end of the article.

This is a guest contribution from Kelvin Tran of Litimetrics. Further details about the author can be found at the end of the article.Since 2010, there have been 472 patent proceedings filed in the Federal Court of Australia. During the same period, there were over 160,000 standard patents granted, and over 1,400 innovation patents certified. On those numbers alone, the chance that an applicant or even opponent will be involved in Federal Court litigation is therefore rare. It’s obvious why - litigation is expensive and lengthy, and litigants, for the most part, are sensible.

Most rights-holders know that litigation only makes sense when the commercial value of the rights to be enforced exceeds the costs of litigation. But rights-holders often can’t accurately estimate the true costs of litigation. Litigation therefore also occurs because the parties lack information to make fully informed decisions about whether the value of the rights to be protected outweigh the costs to protect them (i.e. the costs of litigation). This cuts both ways – those who underestimate the cost and length of litigation might litigate where alternatives make better economic sense, while those who overestimate fail to litigate when it is the optimal strategy.

The source of uncertainty is clear – comprehensive and comprehensible data is not readily available. In this piece, I use data compiled by Litimetrics to look at trends associated with Federal Court patent litigation. I rely on data:

- that Litimetrics collects about Federal Court patent litigation from electronic court dockets;

- from IP Australia itself (e.g. via IPGOD and AusPat); and

- from the published judgments, mined by Litimetrics.

- 2013 and 2014 were the busiest recent years for patent litigation in Australia;

- the median duration of patent litigation that proceeds to a trial and final judgment is over three years;

- cases that settle prior to trial, however, have a median duration of 210 days;

- many events punctuate typical patent proceedings – directions hearings alone, for example, average over 16 per proceeding; and

- once the trial is over, litigants can expect to wait a number of months for a decision in a patent case.

The Busiest Periods for Patent Litigation

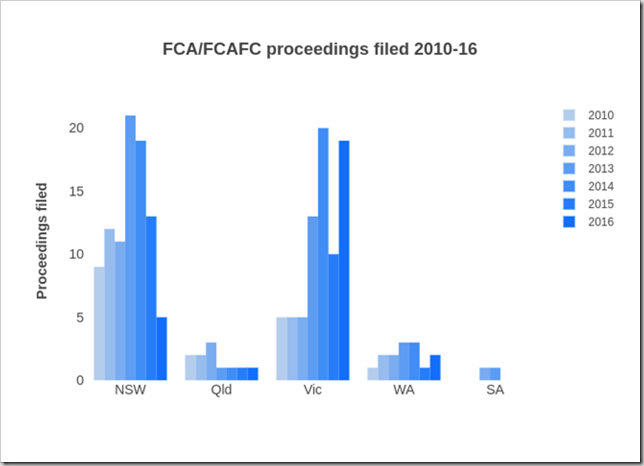

The chart below shows the total number of proceedings commenced in each of the District Registries, between 2010 and 2016.

It should be no surprise that the majority of applicants choose to file proceedings in the NSW and Victoria District registries. Filings in Western Australia and Queensland are far behind. This split across registries roughly reflects the breakdown of judges assigned by the Federal Court to the Intellectual Property - Patent National Practice Area, which probably itself reflects the distribution of the population and industry across states and territories in Australia.

Grouping filing data by the date proceedings were commenced, we can see that 2013/2014 were busy periods, with over 50 proceedings being filed. More recently, filing levels have reduced to the levels in 2012.

What Is the Duration of Patent Proceedings?

The duration of litigation is obviously concerning to the parties involved, regardless of the subject matter. As a solicitor, it was probably the most common question clients would ask when deciding whether to commence proceedings. Litigation necessarily means the incurring of external counsel costs and distraction of employees required to dedicate time to litigation instead of other productive tasks. In patent litigation, where appeals might be against a decision of the patent office pre-grant (i.e. before the ability to exploit), delay in resolving litigation also means delay in realising the commercial value of patent rights.Although litigation is rare, at least when compared to the number of patent applications, once you’re involved, it’s likely you’ll be there for a while. It’s a point to bear in mind when weighing up litigation. First, the proceedings are lengthy, and secondly, they could be extended by appeal.

Between 2004 and 2017, there were 505 finalised patent proceedings (see the methodology in the Appendix for how I’ve defined a ‘proceeding’ for the purposes of this section). The longest was Doric Products Pty Ltd v. Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd, which many readers will be aware is one of the most famous and important patent disputes of the 2000’s, having gone to the High Court not once, but twice, on inventive step and again on ‘fair basis’. The median length of 331 days, by comparison, seems to be relatively short.

We can look at a scatter plot of the durations to see if there’s any discernible trend. To do so, I’ve plotted the proceedings:

- By termination date (with a 2016 cut-off) rather than date of filing to avoid the possibly misleading exclusion of recently filed but still pending proceedings, i.e. the longer durations – there are in fact 63 pending-proceedings that were filed in 2016. (For example, if I plotted by date of filing, we’d see a bunch of shorter-duration cases towards the end of the chart as the longer proceedings filed at the same dates would not yet have been finalised or represented on the chart.)

- From 2008 onwards to avoid biases that would be introduced if I started from the date proceeding data is available (2004) and omitted the proceedings earlier filed (for which I don’t have data) but that were ongoing. That is, I’d be omitting some lengthy proceedings terminated in 2004 and after, bringing the average down.

In October 2016, the Court implemented the National Court Framework reforms to facilitate the just resolution of disputes as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. Because it’s only been about a year and a half since the reforms, it’s likely too early to tell whether the reforms have had any meaningful effect on durations of patent proceedings. As set out above, there are still 63 patent proceedings filed in or after 2016 that have not yet been finalised. The duration of these proceedings, which would have been the first to benefit from the reforms, may be informative. I suspect though that durations will remain unchanged. This is because the length of many patent cases is driven by the need to adduce extensive expert evidence, which is a step that cannot be easily expedited.

There’s also the possibility of the litigation being extended by appeal. In this article, however, I focus only on first-instance decisions, leaving a more-detailed analysis of appeals for another time.

Most Cases End in Settlement

Measuring the number of proceedings that end with a substantive written judgment is complicated by the fact that interlocutory and final judgments are not readily distinguishable from the Federal Court eDocket. Using a heuristic to identify final judgments (judgment handed down within a month of the finalisation of the proceeding, and at least 3 months since the date of commencement), I find that about 96 of the 296 finalised patent proceedings filed since 2010 (or approximately 32%) ended with the Court handing down a final judgment. To put it conversely, two-thirds of Federal Court patent proceedings settle before the issuing of a final or substantive judgment.A significant number of all patent proceedings therefore ended with the Court handing down a written judgment. This number is significantly higher than the proportion of written judgments resulting from other Federal Court proceedings. If I exclude patent proceedings, and use the same methodology, only 15% of Federal Court proceedings end in a written judgment.

Settlement Saves Time (and Money)

Not surprisingly, proceedings that end with the handing down of a written judgment last longer than those that settle. The median length to reach finalisation by written judgment, 1,183 days, is almost 6 times the median length of proceedings that settle without a written judgment, 210 days.

Most of this additional time is taken to prepare for trial, not the trial itself. The median number of days elapsed before the start of trial is 525 days (over a year and a half), with a variance of 241 days. Many of you will know that patent cases are heavily dependent upon highly technical expert evidence. The process of preparing expert evidence is what consumes much of the preparation time, and contributes greatly to the cost of litigation. For litigants, this should serve as a strong incentive to settle, or at least should be taken into account when considering settlement offers.

Trials, by contrast, are relatively short. Even excluding one-day trials (which are numerous and which I class as interlocutory, or at least summary, in nature), close to half the trials are less than 10 days in length, and a quarter are between 10 and 20 days. This makes some sense – court time is a scarce resource in litigation. Trial preparation minimises the drain on this resource.

When to Expect a Judgment

Some of the duration of a case, if not settled, is due to the time taken by the court to hand down judgment (i.e. the reserved time, being the time between the last hearing date and the date judgment is formally delivered). Litigants are often surprised at how long this can take, and I’m sure every practitioner out there has been asked about when to expect judgment to be handed down. Looking at the same set of cases, the median reserved time is 140 days, or about four and a half months.Other Statistics On Patent Proceedings

What happens before the case is finalised? I answer this question by looking at the events occurring in patent litigation and averaging them out across the number of proceedings filed. The average number of directions hearings may seem staggering, but for anyone who’s been involved in litigation, a rate of about one per month over the course of a proceeding is the standard.

Event

|

Number

|

Average per proceeding

|

Affidavit/witness statement

|

4,408

|

6.9

|

Directions hearing/conference

|

10,700

|

16.9

|

Amended document filed

|

972

|

1.5

|

Substantive hearing

|

659

|

1.0

|

Interlocutory applications

|

1,595

|

2.5

|

Return of subpoenas

|

560

|

0.9

|

Submissions

|

997

|

1.57

|

Returning to durations, I’ve plotted the pendency of a proceeding against the time since filing. In my experience, initial survival is something the applicant wants (i.e. to avoid strike outs and summary dismissals), but past this stage settlement is almost always commercially sensible. Curiously, proceedings filed in NSW seem to have a better survival rate than proceedings in Victoria. It’s possible that proceedings filed in NSW, being, anecdotally, the preferred jurisdiction for important cases, are better funded and better able to weather litigation, but this is a guess. The greatest gap is at about 15 months, where there’s a 10% difference in survival rate between the two groups of proceedings.

Concluding Notes

This general analysis of patent litigation in the Federal Court is unlikely to clear up all uncertainties about Federal Court patent litigation. As lawyers often say, it depends on the circumstances of the case. But knowing that the median length of a proceeding doubles if not settled, and the time it takes to reach trial, should, however, help to inform thoughts about litigation strategy. Isolating those insights to particular parties, law firms and venues may be more helpful – and is what we try to do with data at Litimetrics. If you’re interested in using the data for your own internal purposes, please reach out – our goal is to help organisations make better data-driven decisions.

About the Author

Kelvin Tran is a former ABL and Minter-Ellison litigator and now the CEO of Litimetrics Inc. Litimetrics helps litigants and lawyers in Australia, the US and the UK make use of data mined from court records. In Australia, Litimetrics’ data-driven tools help barristers, solicitors and litigants to get insights about the duration of cases and the experience of particular law firms, lawyers and patent attorneys, and to quickly find citations missing from their submissions and advices.

Kelvin Tran is a former ABL and Minter-Ellison litigator and now the CEO of Litimetrics Inc. Litimetrics helps litigants and lawyers in Australia, the US and the UK make use of data mined from court records. In Australia, Litimetrics’ data-driven tools help barristers, solicitors and litigants to get insights about the duration of cases and the experience of particular law firms, lawyers and patent attorneys, and to quickly find citations missing from their submissions and advices.

Appendix: Methodology

Proceeding counts

Applications within proceedings are treated as separate proceedings, as are related proceedings with different file numbers. For example, in the Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp & Anor v Apotex Pty Ltd (NSD936/2012) matter, there are two applications (which I treat separately). I do this to represent the complexity of the particular litigation and to account for the different durations of the applications – in the example, the cross-claim was commenced after the originating application, meaning it has a shorter duration.When I examine judgments, I take the more traditional approach of treating each file number as a proceeding (whether the eDocket lists multiple applications or not). This is to prevent double counting of judgments (as far as is possible).

Classification of proceeding as patent proceeding.

I classify a proceeding as being a patent dispute where it is classified as ‘Intellectual Property (Patents)’ upon filing with the Federal Court of Australia, or where otherwise or machine learning classifiers designate the proceeding as involving patent law issues (above a certain weight).I exclude appeals against the Commissioner in the data, which I consider to be in the nature of an extension of the patent prosecution phase, but include appeals from opposition proceedings.

Duration

I measure the duration of a proceeding from the date filed and the date terminated, as specified on the Commonwealth Courts Portal.The duration of a trial is measured from the first hearing date to the last hearing date specified on the judgment, if a judgment is handed down.

Outcomes

I infer outcomes of a proceeding from the status of dockets, mapped per the table below.| Status/concluding event | Inferred result |

| Finalised - Granted/Allowed | Applicant/appellant favourable |

| Finalised - Dismissed | Respondent favourable |

| Finalised - Granted/Allowed in Part | Neutral |

| Finalised - Resolved | Neutral |

| Finalised - Discontinued/Withdrawn | Neutral |

| Finalised - Granted/Allowed by Consent | Neutral |

| Finalised - Dismissed By Consent | Neutral |

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment