An article posted on 24 October2016 on the IP Watchdog blog caught my attention. It is by Mark Schultz and Kevin Madigan who have recently authored a report for the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP), The Long Wait for Innovation: The Global Patent Pendency Problem [PDF, 1MB]. Their thesis – and it is a sound one – is that the growth in numbers of patent applications throughout the world over the past decade or so is stressing the resources of many patent offices, and is resulting in a growing backlog which is resulting, in turn, in excessive pendency (i.e. the delay between filing an application and a patent actually being granted). This, say Schultz and Madigan, is a problem, because in some countries patents are taking so long to issue that, by the time they do, they may be of little value to their owners.

An article posted on 24 October2016 on the IP Watchdog blog caught my attention. It is by Mark Schultz and Kevin Madigan who have recently authored a report for the Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP), The Long Wait for Innovation: The Global Patent Pendency Problem [PDF, 1MB]. Their thesis – and it is a sound one – is that the growth in numbers of patent applications throughout the world over the past decade or so is stressing the resources of many patent offices, and is resulting in a growing backlog which is resulting, in turn, in excessive pendency (i.e. the delay between filing an application and a patent actually being granted). This, say Schultz and Madigan, is a problem, because in some countries patents are taking so long to issue that, by the time they do, they may be of little value to their owners.The Long Wait looks, in particular, at the pendency of patents granted by a representative sample of 11 offices, between 2008 and 2015. The results place South Korea, China, Australia, USA and Japan in a ‘low pendency’ group (application to grant in under four years). Egypt, the European Patent Office (EPO), Argentina and India fall into a ‘medium pendency’ group (between four and eight years). Bringing up the rear, in a ‘high pendency group’ (eight to 12 years) are Brazil and Thailand.

Schultz and Madigan’s conclusion that patent offices with longer pendency are struggling, while those with the lowest pendency are doing fine, is broadly valid. However, there are a couple of limitations to their approach, as a result of which they miss some subtle – and not-so-subtle – points regarding the performance of a number of the patent offices in their study.

First, using pendency as a measure of performance is inherently backward-looking. For the offices in the ‘high pendency’ group, in particular, the applications in question were filed, on average, a decade prior to the year in which they were granted. But what does this mean for applications filed since 2005? Can they expect a similar, shorter, or longer pendency?

Second, the assumption underlying the methodology – that pendency is primarily a result of patent office delays resulting from an existing backlog of applications – is not entirely valid in relation to a number of the patent offices considered. Applicant behaviour and specific legal and regulatory provisions are also significant factors in some jurisdictions. Indeed, in Australia and Japan in particular the impact of changes in laws and/or regulations are clearly visible in the results, and dominate over patent office examination delays.

By looking at filing and grant behaviour in the 11 offices selected by Schultz and Madigan, in conjunction with their pendency data, it is possible to obtain further insights. For example:

- the Brazilian and Thai patent offices are in very serious crisis (the term ‘basket case’ would not be inappropriate) – in the absence of major intervention the pendency of applications in these offices will continue to grow (and the apparent reduction in pendency in Thailand between 2012 and 2014 appears to be an anomaly);

- although the EPO falls into the ‘medium pendency’ group, it appears to have its workload under control, and is at low risk (along with Australia, the USA, Korea and Japan) of developing a growing backlog;

- within the ‘medium pendency’ group, the Indian Patent Office appears to be at greatest risk of joining Brazil and Thailand in the ‘high pendency’ group, with every indication that the growth in pendency observed in Schultz and Madigan’s study will not just continue but, without action, accelerate; and

- China, despite falling in the ‘low pendency’ group is, on other measures, on par with Argentina, and may be starting to develop a growing backlog of applications.

How Applicant Behaviour Affects Pendency

In all jurisdictions applicants can exercise some control over the pace of processing of their patent applications. In particular, whenever an office action (e.g. an examination report) is issued, the applicant has some fixed time period within which to respond and/or to overcome all of the matters raised in the action and secure allowance of the application. This period is commonly between three and 12 months, depending upon the country.Furthermore, in many jurisdictions the applicant has some degree of control over when the examination process actually commences. For example, in countries including Australia, Japan, China and Korea, and at the EPO, it is necessary for the applicant to file an explicit request for examination, and pay a corresponding fee, which is separate from filing of the application itself. The deadline for filing such a request varies depending on the jurisdiction, but is typically between three and five years from filing. Significantly, up until 2001 the examination request deadline in Japan was seven years after filing, at which time it was reduced to three years.

For those who deal primarily with the US system, it often comes as a surprise that most applicants elect to delay examination for as long as possible. However, this is a very common practice, in large part because it delays the associated costs of examination. Additionally, by exercising control over the commencement of examination, applicants are able to take advantage of outcomes in higher-quality offices (such as the USPTO) in order to expedite subsequent proceedings in other jurisdictions.

As a result, it is important to account for applicant behaviour in those countries in which an explicit, separate, request for examination is required. In particular, pendency in these offices comprises an ‘applicant’ component, corresponding with the average delay in filing a request, plus an ‘office’ component, comprising the average time subsequently required for completion of examination.

Impact of Changes in Laws and Regulations

Changes in the patent laws, and the rules governing the application process, can also compel or encourage changes in applicant behaviour.As I mentioned above, the examination request deadline in Japan was seven years from filing prior to 2001, at which time it was reduced to three years. However, the new deadline applied only to applications filed on or after 1 October 2001. It was therefore still possible for an applicant who had filed an application on 30 September 2001 to delay their examination request until 30 September 2008.

In Australia, the commencement of the Raising the Bar law reforms on 15 April 2013 gave applicants an incentive, where possible, to file their applications and request examination prior to this date, rather than delaying examination, as is more common under normal circumstances.

Schultz and Madigan’s Pendency Data

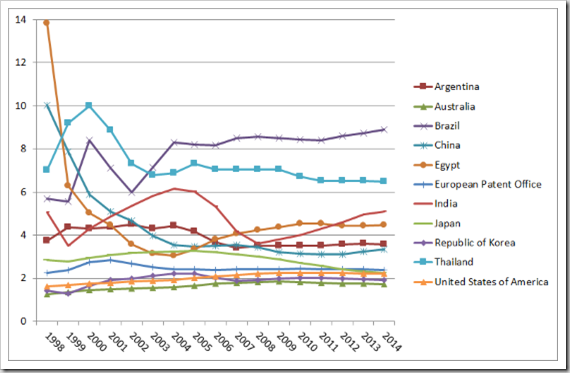

The chart below is reproduced from Figure 2 of The Long Wait, and shows the trends in patent pendency, i.e. the average pendency, in years, of applications granted in each office, between 2008 and 2015.

One feature of these results that is immediately noticeable is the dramatic decline in pendency in Japan, from over six years in 2008 to under four years in 2015. This can, however, be explained almost entirely by the change in the deadline for making a request for examination in 2001. It was only in 2009 and beyond that applications subject to the seven year deadline could finally be completely flushed from the system, and of course this did not happen overnight.

In Australia, a decline in pendency is observed from 2013 onwards. This can be explained by an increase in ‘early’ examination requests prior to the introduction of higher standards of patentability on 15 April of that year, in combination with an increase in the number of examiners employed by IP Australia in anticipation of the corresponding spike in demand. As a result, pendency has fallen without any corresponding growth in the backlog of unexamined applications.

The dramatic oscillations in pendency in Egypt are also notable. Although Schultz and Madigan do not offer any specific explanation for this, they do rightly note that over the period in question Egypt could be regarded as a ‘developing country weathering historical challenges’.

An Alternative Measure of Examination Performance

In an effort to obtain more insight into the performance of the various patent offices considered in the Schultz and Madigan study, I retrieved data on the numbers of applications filed, and patents granted, between 1998 and 2014 (the most recent year for which figures are available) from the IP Statistics Data Center maintained by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).The chart below shows the number of applications filed each year, in each office, via either direct or PCT national phase filing. I have used a logarithmic scale, in view of the very large disparity in filing numbers between offices and across the time period covered.

China and India have each experienced around a tenfold increase in applications over the past decade-and-a-half. Numbers in other jurisdictions have been more stable, although the general trend is upwards, except in Japan.

Year-on-year patent grants are shown in the following chart, again on a logarithmic scale.

It is immediately apparent from this chart that the oscillations in application pendency at the Egyptian Patent Office correspond with low grant rates in 2005-6. It appears that a drop in examinations during this period may have resulted in a growth in the backlog of applications. This backlog then manifested as additional pendency for the applications that were ultimately granted five or so years later. The more recent rise in pendency may be correlated with the stagnation in grants between 2008 and 2010 following a period in which application rates recovered strongly from a dip in 2004.

I also note that there are ‘gaps’ in the grant data for Brazil. I am unsure of the origin of these gaps, which were present in the WIPO dataset.

The very large scale differences make it difficult to compare the application and grant data from the various patent offices. I have therefore computed a value that I call the backlog metric. This is obtained by computing the cumulative number of applications filed in each office, starting with the first year in the dataset (1998), and dividing by the corresponding cumulative numbers of patents granted. The backlog metric is thus a measure of the total number of applications filed relative to the total number of patents granted during the period covered by the data.

A large value for the backlog metric implies that the number of applications filed, over time, significantly exceeds the number of patents granted, implying that the backlog of applications awaiting disposal is growing, which I would expect to result in an increase in pendency.

The backlog metric for the 11 patent offices, based upon the above application and grant numbers is shown in the following chart.

The best performing patent offices (Australia, Korea, USA, Japan and EPO) all have a backlog metric of around 2. Although this implies that twice as many applications are being filed as there are patents granted, over time, it does not mean that the backlog is growing. There is, for one thing, a delay built into the data, in that granted patents were typically filed a number of years earlier, during which time the number of applications has been increasing annually (other than in Japan). In addition, not all applications result in granted patents.

Interpreting the ‘Backlog Metric’

When considered in combination with the actual pendency data in Schultz and Madigan’s results, it is apparent that those offices with a backlog metric below 3 are generally maintaining consistent, and relatively low, pendency, and vice-versa.There are, however, a couple of notable exceptions to this ‘rule’. First, the EPO has a low backlog metric of 2.4, despite falling into Schultz and Madigan’s ‘medium pendency’ group. This suggests that the longer pendency at the EPO is structural in nature, i.e. it is effectively ‘built-in’ to the system, and is not the result of underperformance on a year-to-year basis. Based on filing and grant numbers, the modest growth in pendency between 2008 and 2015 does not appear to be anything to be greatly concerned about.

An office to watch could be China. While Schultz and Madigan have it comfortably within the ‘low pendency’ group, it has started to exhibit an increase in the backlog metric in recent years, which could be indicative of a failure to keep pace with rapidly growing-application numbers.

While India was showing a decline in its backlog metric between 2004 and 2008, it has since been climbing steadily. As of 2014, it had accumulated more than five times as many applications filed as patents granted. Average pendency in India is at almost eight years, and rising, and the backlog metric unfortunately suggests that this is only going to continue to rise.

Finally, Thailand and Brazil are, as I noted at the outset, pretty much basket cases. Every indicator is pointing towards disaster for these offices. They have long average pendency, equivalent to half the patent term and higher. They are experiencing ongoing growth in patent filings. Both also have high backlog metrics – as of 2014, 6.5 in the case of Thailand and 8.9 in the case of Brazil. Applications therefore continue to pour in, with only a small proportion being finalised.

Conclusion – Where Not to Bother Filing?

Of the 11 patent offices considered by Schultz and Madigan, and in the present analysis, there are six in which applicants can feel fairly confident of seeing their applications examined and (hopefully) a patent granted within a reasonable time frame: Australia; South Korea; the USA; Japan; China; and the EPO. Furthermore, most of these offices provide mechanisms, such as accelerated examination and/or Patent Prosecution Highway (PPH) programs, that enables applicants to obtain even faster should they wish to do so.There are, however, signs of some strain in the Chinese Patent Office, although it must be kept in mind that this is in the face of a ten-fold rise in applications filed over the past 15 years. Some increase in backlog is therefore to be expected, as the Office doubtless struggles to hire and train new examiners to keep up with the growth.

At the other end of the spectrum, anybody filing an application today in Brazil, Thailand or India may have good reason to be concerned that by the time a patent is granted, it may not have much – if any – of its 20-year term remaining! All the indicators point to ever-increasing pendency of applications in these countries.

Schultz and Madigan provide some suggestions as to how the problems with pendency may be addressed. I must say, however, that I have some doubts as to whether the worst-performing offices will be able to muster the resources required to address the growing crises that they are facing.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment