As of 24 February 2017, Australian and New Zealand patent attorneys (collectively ‘Trans-Tasman Patent Attorneys’) have been subject to a single joint regulatory and disciplinary regime administered by the Trans-Tasman IP Attorneys Board (‘the Board’). Among other things, the Board is responsible for maintaining a register of patent attorneys, a searchable version of which is available on its website. The register records details of each attorney including, in most cases, a contact address and the name of any attorney firm or company that employs or is operated by the attorney. This information provides an opportunity to ‘profile’ the trans-Tasman patent attorney profession.

As of 24 February 2017, Australian and New Zealand patent attorneys (collectively ‘Trans-Tasman Patent Attorneys’) have been subject to a single joint regulatory and disciplinary regime administered by the Trans-Tasman IP Attorneys Board (‘the Board’). Among other things, the Board is responsible for maintaining a register of patent attorneys, a searchable version of which is available on its website. The register records details of each attorney including, in most cases, a contact address and the name of any attorney firm or company that employs or is operated by the attorney. This information provides an opportunity to ‘profile’ the trans-Tasman patent attorney profession.While there may be no such thing as an ‘average’ patent attorney, an analysis of the register permits a few statistical observations to be made. For example, if you were to pick a trans-Tasman patent attorney at random, there is nearly a two-thirds probability that they are also registered as a trade marks attorney, around 80% chance that they work as an attorney in private practice, a 95% chance that they live in either Australia or New Zealand, just under 25% probability that they work for a firm with 24 or more other patent attorneys, and about a 30% probability that they are employed by a firm within one of Australia’s publicly-listed ownership groups. There is also around 70% chance (if that is the right word) that they are a man.

There is one registered patent attorney in Australia for every 32,000 population, which compares to one for every 7,000 people in the United States. You would think, therefore, that If the demand for patent attorney services in Australia matched that of the US then Australia’s attorneys would be drowning in work, and the profession would be experiencing explosive growth! Of course that is not the case. On the contrary, the Australian and New Zealand patent attorney professions have been undergoing significant structural changes in response to market challenges. The numbers bear out just how substantial these changes have been in relation to the size of the trans-Tasman profession.

How Many are Patent and Trade Marks Attorneys?

As the Board’s website explains, registration is not required in order to practice in trade mark matters. Anyone can submit trade mark applications to IP Australia or the Intellectual Property Office of New Zealand (IPONZ) on behalf of themselves or another person. There are, however, certain benefits associated with registration, most notably the right to actually call oneself a ‘trade marks attorney’ or ‘trade marks agent’. However, many of the other benefits are conferred upon registered patent attorneys in any event, and all patent attorneys are required to complete the initial educational qualifications necessary to register as a trade marks attorneys.Some patent attorneys also practice in trade mark matters, while others do not. Some of those who carry on a trade marks practice choose to register as trade marks attorneys, while others do not. There are also practitioners – many of them IP lawyers – who do not have the technical background necessary to qualify as a patent attorney, and who practice in trade mark matters, also variously with or without formally qualifying and registering as trade marks attorneys. It should also be noted that New Zealand has never had a formal system of trade marks attorney registration, and thus registration as a trade marks attorney is primarily beneficial for those wishing to practice before IP Australia.

The chart below shows the breakdown of attorneys registered as patent attorneys only, as trade marks attorneys only, and as both patent and trade marks attorneys. Of the 1469 registered attorneys, 25% are registered only as patent attorneys (I am included in this group), 31.5% are registered only as trade marks attorneys, and 43.5% are registered as both patent and trade marks attorneys.

I was actually surprised at the relatively high proportion of registered patent and trade marks attorneys. Maintaining both registrations requires payment of an additional registration fee, as well as keeping up with additional annual continuing professional education (CPE) obligations. While a number of larger attorney firms have dedicated trade marks practice groups, allowing their patent attorneys to focus on patents work, in smaller firms it is clearly beneficial for attorneys not only to engage in both patent and trade marks practice, but to be able to promote themselves as patent and trade marks attorneys.

Where Are All the Attorneys?

Of the 1004 registered trans-Tasman patent attorneys, 1003 have contact information enabling their country of work and/or residence to be identified. The map and table below summarises the various places around the world where trans-Tasman attorneys may be found.

Unsurprisingly, the vast majority are based in Australia (75%) and New Zealand (20%). The remaining five per cent are scattered thinly across the globe, with the greatest representation being in the UK, and its former colonies of Singapore and Hong Kong (both of which are, notably, territories in which Australian firms have outposts).

In Which Sectors Do Attorneys Work?

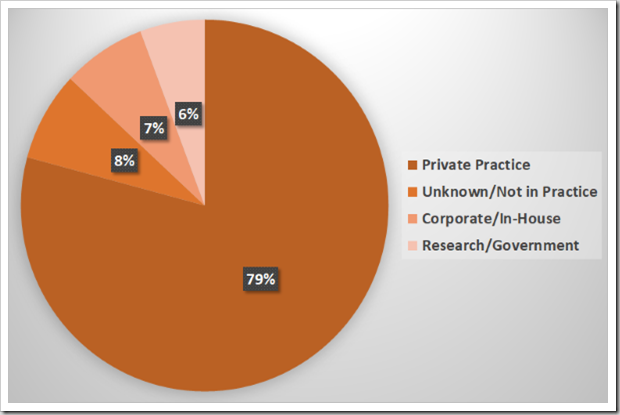

The chart below shows the distribution of trans-Tasman patent attorneys across different sectors of practice. In creating this chart, I assumed that any attorney who has listed a firm name in their registration details – even if it is just a variation of their own name – is actively practicing. Only those with no firm affiliation (including me) have been identified as ‘unknown/not in practice’.

Again, it is no surprise that the vast majority of attorneys are working in private practice, i.e. as sole operators, or in attorney, legal or related service providers. Around 7% are employed in the corporate world, either as in-house attorneys or in some other capacity. A further 6% work in the research and government sectors, mostly as IP practitioners within universities and CSIRO, with a few working in other state and federal government departments or authorities.

Another notable statistic is that fewer than 100 registered patent attorneys work in corporate, research, or government roles in Australia, with a further 20 in such roles in New Zealand. These are not encouraging numbers for attorneys who do not wish to work in private practice. They are also consistent with the rather dispiriting observation that very few corporates in Australia are engaged in levels of technical IP generation and protection that would justify employing in-house patent practitioners.

How Big Are Trans-Tasman Patent Practices?

The chart below shows a breakdown of private-practice patent attorney numbers by the size of the practices in which they work. More than a third of all identifiable private-practice attorneys work for firms employing 25 or more trans-Tasman patent attorneys. There are only eight firms in this category, thus each employs, on-average, 40 attorneys.

A slight majority of the remaining registered patent attorneys work either by themselves, or with no more than two other registered attorneys, although an almost-equal number work in small and mid-size firms. It should be noted that these figures consider only the number of registered trans-Tasman patent attorneys within an organisation. There are some very large law firms, for example, that employ only a small team of patent attorneys. Nonetheless, the vast majority of small patent attorney practices are small firms and sole operators.

Across all sizes of firm, there are in excess of 220 identifiable, distinct patent attorney practices across Australia and New Zealand, ensuring that users of patent attorney services should have a wide choice of different service styles and price points.

How Many Attorneys Are Public versus Private?

Towards the end of 2016, I estimated that roughly a quarter of Australia’s patent attorneys would be ‘publicly owned’ – or, more accurately, employed by firms within ownership groups listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) – by February 2017. Since then, the trans-Tasman attorney regime has commenced, bringing more New Zealand attorneys onto the register. In October 2017 IPH Ltd (ASX:IPH) announced the first acquisition of a New Zealand firm – A J Park – by an Australian listed group.The chart below summarises where we now stand with regard to registered patent attorneys working within publicly-listed groups. Of all trans-Tasman patent attorneys identifiably working in private practice, around 35% are employed within listed groups. A similar proportion work in privately-held firms with four or more practicing patent attorneys, and a slightly lower number work in solo or small privately-held practices with no more than three patent attorneys.

While this looks like a reasonable distribution of attorneys, offering clients ample choice between ‘public’ and ‘private’ models, at the top end of the market the numbers are somewhat more skewed. A client seeking the services of a larger firm has a relatively smaller choice of attorneys within privately-held practices, assuming that this is a consideration. Among firms with 25 or more patent attorneys, 71% of registered attorneys are employed within publicly-listed ownership groups. The position is better if mid-sized firms are also in contention – within practices having between 10 and 24 patent attorneys, 58% of attorneys are employed by privately-held firms.

Gender (In)Equality

I used the (free) genderize.io API to assign a gender to each registered attorney based on given names. In 110 cases in which the genderize service produced a null or uncertain result (mostly non-English and gender-neutral names) I endeavoured to determine gender from personal knowledge, firm websites, or LinkedIn profiles. No doubt this methodology is subject to criticism, and I have no desire to ‘impose’ a gender on any particular individual, however I felt that this profile would be incomplete if I did not attempt to determine the overall gender mix of the profession.Registered trans-Tasman patent attorneys are 30% female and 70% male. The statistics are almost identical for the subset of patent attorneys who are also registered as trade marks attorneys. However, for the 465 individuals registered only as trade marks attorneys, the mix is 56% to 44% in favour of female attorneys.

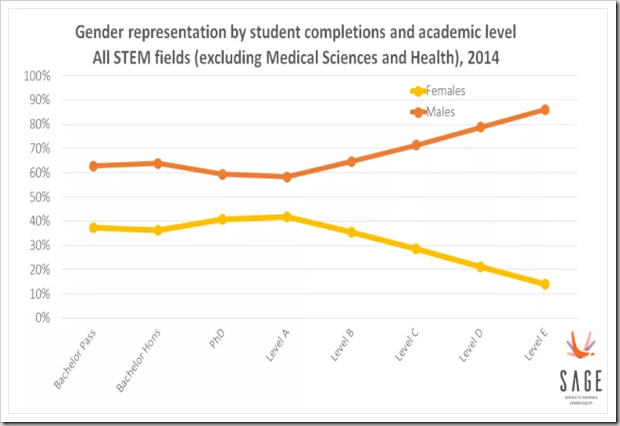

There is clearly a significant gender imbalance in the patent attorney profession. In some ways, this is not at all surprising. In order to qualify as a trans-Tasman patent attorney it is necessary to possess a tertiary qualification in a field of technology that contains potentially patentable subject matter involving a depth of study that Board considers sufficient to provide a foundation for practice as a patent attorney. In practice, therefore, most registered patent attorneys have degrees in either science or engineering. According to figures collated by Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE), in 2014 there were 220,162 total students studying in a STEM (‘Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics’) bachelor degree, of which 33% were women and 67% men.

On one level, therefore, the gender imbalance in the patent attorney profession merely replicates the imbalance in the underlying technical disciplines. Obviously the issues around gender parity are complex, and I do not intend to get into them here. For a more in-depth analysis, I recommend an excellent series of articles published last year by Queensland-based patent attorney (and engineer) Katherine Rock under the heading Where are the female patent attorneys? Part 1: The business case for gender balance; Part 2: Debunking the myths; Part 3: What does the evidence say about causes?; and Part 4: Opportunities for change.

Conclusion – Concerns for the Future of the Patent Profession?

It is my opinion that any country that hopes to foster innovation, and the successful development, commercialisation, and export of IP and IP-intensive products and services, requires a strong, highly-skilled, and diverse patent profession. While there are, of course, well-qualified IP professionals in all significant jurisdictions, Australian innovators – and particularly SMEs that cannot justify the cost of in-house attorneys – need skilled advisors ‘at home’ who can guide them through the complexities of identifying, managing, and protecting their intellectual property in Australia and other relevant jurisdictions.Australia is a country of over 24 million people, but with fewer than 750 registered patent attorneys – a ratio of around 32,000 people per attorney. By comparison, the United States has a population of nearly 330 million people, and (according to the USPTO’s Office of Enrollment and Discipline) just under 46,000 active patent attorneys and patent agents – a ratio of just over 7,000 people per attorney.

Yet, despite the fact that on these figures there should be many more potential clients per attorney in Australia than in the US, patent filing activity by Australian residents is relatively low, and shows only marginal growth, creating a challenging market for local patent attorneys. While there are many small firms, partnerships, and solo practitioners operating in Australia, it is the mid-sized and larger firms that have traditionally been the ‘engines’ of the Australian patent profession. These are the firms that can afford to employ and train future generations of attorneys, and that provide an environment in which early-career attorneys are able to gain exposure and experience with a range of local and overseas clients and IP registration regimes.

It is these mid-to-large-sized firms, however, that appear to be facing the greatest challenges, and undergoing significant structural changes in response. And while I do not see the recent emergence of the ‘ownership group’ model, or public listings of holding companies, as necessarily negative, there is no question that this is a somewhat bold experiment that must create some uncertainty around the future of the profession. The figures show that well over half of the positions in medium-to-large firms are now within these publicly-listed ownership groups. The impact of this (if any) on the training and development of new attorneys is yet to be seen.

The more fundamental underlying problem, of course, is that despite policy initiatives with encouraging names like The National Innovation and Science Agenda, Australia continues to underperform in the development and commercialisation of technological innovation. Furthermore, Australian companies and individuals generally have a poor understanding of IP, and little appreciation of the value of IP rights. Indeed, for most of these companies IP protection continues to be viewed as an expense that is best minimised – or completely avoided – rather than a means of securing valuable intellectual assets. Until these issues are addressed, there is unlikely to be any significant increase in demand for patent attorney services in Australia.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment