On 27 November 2018 QANTM IP Limited (ASX:QIP) and Xenith IP Group Limited (ASX:XIP) announced that they have entered into an agreement to merge through an all-scrip scheme of arrangement. The merger is subject to approval by a court, and by Xenith shareholders. If it goes ahead (as seems likely), each Xenith share will be exchanged for 1.22 QANTM shares. Existing QANTM and Xenith shareholders will end up owning 55% and 45%, respectively, of the merged group, which will comprise five Australian specialist IP firms (Davies Collison Cave, FPA Patent Attorneys, Griffith Hack, Shelston IP and Watermark), along with IP valuation, innovation and advisory service provider Glasshouse Advisory (currently owned by Xenith IP) and Malaysian IP firm Advanz Fidelis (which was acquired by QANTM IP in June 2018).

On 27 November 2018 QANTM IP Limited (ASX:QIP) and Xenith IP Group Limited (ASX:XIP) announced that they have entered into an agreement to merge through an all-scrip scheme of arrangement. The merger is subject to approval by a court, and by Xenith shareholders. If it goes ahead (as seems likely), each Xenith share will be exchanged for 1.22 QANTM shares. Existing QANTM and Xenith shareholders will end up owning 55% and 45%, respectively, of the merged group, which will comprise five Australian specialist IP firms (Davies Collison Cave, FPA Patent Attorneys, Griffith Hack, Shelston IP and Watermark), along with IP valuation, innovation and advisory service provider Glasshouse Advisory (currently owned by Xenith IP) and Malaysian IP firm Advanz Fidelis (which was acquired by QANTM IP in June 2018). Based on the closing share price of QANTM and Xenith on 26 November 2018, the merged group would have a market capitalisation of A$285.2 million, which still places it well behind the original listed Australian IP group, IPH Limited (ASX:IPH), which had a market cap of A$1.11 billion as at close of trading on 30 November 2018.

An additional interesting piece of information to fall out of the QANTM/Xenith announcement is the fact that IPH had itself been courting QANTM with a view to a possible merger or acquisition. In an ASX announcement on 27 November 2018, in response to ‘media speculation’, IPH confirmed making a number of approaches to QANTM on the basis of non-binding, conditional proposals, culminating on 20 November 2018 with a proposal with an equivalent value of A$1.80 per QANTM share (a notional premium of 37.4% over the A$1.31 at which QANTM shares were trading on that day). QANTM countered by announcing that its Board did not consider this proposal to be in best interests of its shareholders, due to its ‘highly conditional’ nature and ‘significant execution risk’.

All this would appear to confirm something that I have long suspected – that the Australian market is not big enough to sustain three publicly-listed groups of IP service providers. IPH obviously saw QANTM as a potential acquisition target, while QANTM clearly did not wish to be acquired on IPH’s terms! Instead, QANTM and Xenith have decided that they will be stronger together than they are separately.

But why is it such a struggle for these groups to flourish in the Australian market? One advantage of the public listing of these companies is that, through their annual reports, there is now far greater transparency than ever before in respect of the financial performance of IP services businesses. In combination with publicly-available data on Australian filings for IP rights, this provides useful insights into where the revenues – and profits – are coming from. I have looked at these numbers, and I am afraid that my conclusions are not rosy. The Australian market appears to be stagnant, with firms struggling to enhance profitability. Growth in the listed groups has come through acquisitions rather than genuine new business, with revenues per professional staff member being pretty consistent across the industry. Low-value, transactional work, which ought to have the greatest exposure to competition and downward price pressure, continues to be significantly more profitable than high-value, bespoke services. Yet, despite the obvious challenges and risks that these circumstances present, as far as I can tell firms are continuing to do the same old things that they have done for years, in terms of professional staff management and marketing, with the predictable result that nothing much is changing.

QANTM/Xenith – More Filings, but Less Profit, than IPH

A merged QANTM/Xenith group would, on recent numbers, command a larger share of Australian patent, trade mark, and registered design filings than the IPH group. According to figures in an investor presentation [PDF, 939kB] prepared by QANTM and Xenith, between July 2017 and June 2018 firms in the two groups were responsible for filing 31% of Australian patent applications (provisional, standard, national phase entry and innovation), 21% of all trade mark applications, and 24% of all applications for design registration. This compares with 24%, 15%, and 18%, respectively, filed by firms in the IPH group. Furthermore, in the 2017 calendar year, QANTM/Xenith firms filed 28% of all Australian-originating international patent applications under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), compared with only 14% by IPH firms.It is interesting to compare the above filing figures with the numbers of registered trans-Tasman (i.e. Australian/New Zealand) patent attorneys employed with the respective groups. Based on the content of the official Register as at 11 November 2018, 151 patent attorneys were employed by firms in the QANTM (72) and Xenith (79) groups, compared with 96 patent attorneys employed within the IPH group firms of Spruson & Ferguson, Pizzeys and A J Park. (Note, however, that A J Park is a New Zealand-based firm, and its 37 registered patent attorneys are responsible for relatively few direct filings in Australia.)

Counting only Australian-based attorneys, IPH firms employ just 39% of the number of patent attorneys employed by QANTM/Xenith firms, yet achieve about 68% of the number of Australian filings, across all rights. Considering only patent filings, this proportion rises to 77%, i.e. on a per-attorney basis, IPH firms are responsible for filing twice as many Australian patent applications as QANTM/Xenith firms. Furthermore, IPH firms appear to be significantly more profitable than QANTM/Xenith firms. Based on figures published in its annual reports, the profit margins in IPH’s Australian and New Zealand IP services businesses over the past two financial years – computed simply as net earnings before income tax, amortisation and depreciation (EBITDA) divided by total revenue – have been 41.1% (FY2017) and 34.9% (FY2018). By comparison, QANTM’s profit margins have been 13.0% (FY2017) and 16.7% (FY2018), while Xenith’s have been 11.1% (FY2017) and 14.3% (FY2018 – this is an ‘underlying’ figure that does not include a one-off ‘impairment charge’ of A$20.7 million taken in respect of the carrying value of the Griffith Hack and Glasshouse Advisory businesses).

How Can More Filings Produce Less Profit?

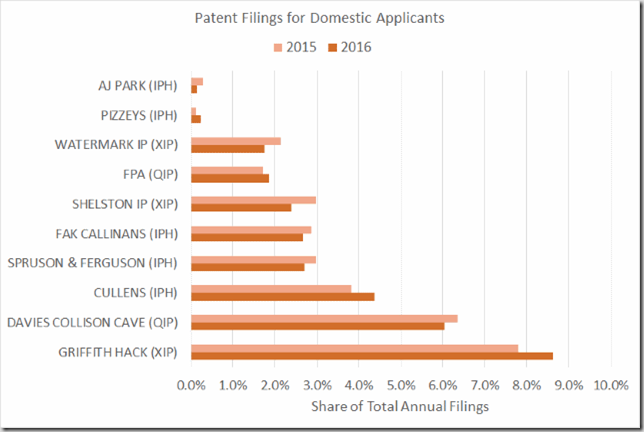

To understand what is going on here, it is necessary to break down the groups’ filing figures according to patent applicant origin. Looking at the performance of the individual firms now making up and/or merged into the listed groups over the 2015-2016 calendar years (based upon data in IP Australia’s 2017 IP Government Open Data release), the shares of patent filings originating from foreign applicants are shown in the following chart.

By comparison, the various individual firms’ shares of filings (including provisional, standard, and innovation patent applications) originating with local – i.e. Australian – applicants is shown in the following chart.

What is clear from the above charts is that the business of IPH firms is significantly skewed towards servicing foreign applicants, relative to the business of QANTM/Xenith firms – especially Griffith Hack and Davies Collison Cave, which dominate filings on behalf of Australian clients. In absolute numbers, in 2016 IPH firms filed 7,670 patent applications on behalf of foreign applicants, and 900 on behalf of Australian clients. In the same year, QANTM/Xenith firms filed 9,740 applications for foreign applicants, and 1,680 on behalf of Australian clients. While this number of foreign-originating applications was around 25% more than for IPH firms, it must be kept in mind that QANTM/Xenith firms employ over 50% more registered patent attorneys, primarily to service a significantly larger share of the domestic market for IP services, as reflected in the Australian client filing figures.

Astute readers might question the above emphasis on patent filing and attorney numbers to the exclusion of other services and staff. However, these figures look to be a pretty good estimator, to a first approximation, of overall performance – perhaps due to other services being proportionate and/or of lower value. In FY2018, for example, IPH’s Australian and New Zealand IP service businesses generated total revenues of A$1.6 million per employed patent attorney, while the combined revenues of QANTM and Xenith businesses were almost the same, at A$1.5 million per employed patent attorney. Furthermore, as has already been noted, profitability is strongly correlated with the total number of patent applications filed per employed patent attorney, with IPH filing twice as many Australian applications per Australian-based attorney, and generating just over twice the profit margin, compared with QANTUM/Xenith.

The Malaise in the Australian Market for IP Services

There is an alarming conclusion that may be drawn from the above numbers: performing transactional, substitutable, and relatively low-value services for foreign applicants is significantly more profitable than providing bespoke, high-value, advice and services for domestic clients. Given that firms in listed groups employ around a third of all actively practising patent attorneys, and account for over half the market for patent attorney services in Australia, it is reasonable to presume that this is true across the entire industry.This is not how things should be. On the face of it, filing and prosecuting patent applications on behalf of foreign applicants – mostly conducted under instruction from overseas attorneys – is a substantially ‘transactional’ business involving lower levels of professional expertise, and higher levels of administrative processing (much of which can and should be automated). This should therefore be a low-margin business, subject to substitution, automation, strong competition and downward cost pressures. On the other hand, servicing a domestic client base, including providing strategic advice, patent drafting, and managing Australian and international IP portfolios, requires significant professional expertise and creativity, and ought to be a high-value, high-margin business. Clearly, this is not the case!

I would suggest that there are two reasons for this. Firstly, routine filing and prosecution services continue to be high-priced, and high-margin, relative to their value. For Australian firms, much of the business in this category is acquired as a result of (sometimes very long-term, and often reciprocal) relationships developed and maintained with associates in foreign attorney firms. Most applicants continue to rely upon their local service providers to advise on, and make arrangements for, foreign filings. This has limited the ability of lower-cost foreign filing service providers to gain direct access to their target market (i.e. the applicants), and thus to compete effectively with established attorney firms. One need only look at IPH’s numbers to see how profitable this business remains for such firms!

Secondly, servicing Australian clients is hard work, and persuading them of the true value of IP services is difficult. I have written before about Australians’ lack of business sophistication when it comes to IP, about the poor appreciation in this country of the value of IP and corresponding decline in per capita patent filings, and about the particular failures of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to identify, manage and protect their IP assets. This is the environment in which Australian IP service providers operate and it can be, frankly, pretty miserable at times. As a patent attorney, it is common to spend a great deal of time educating clients (and prospective clients that never proceed), responding to demanding enquiries, and generally holding clients’ hands through various national and international application processes, in full knowledge that an Australian client is not going to appreciate the real value of these services, or be willing to pay for all the time involved.

All of this ‘unpaid’ work, of course, erodes profitability. And yet, when the relationship with the client is good – and do not get me wrong, it often is – this kind of work exercises the greatest range of an attorney’s skills and experience, and is therefore usually the most rewarding. There are, I would guess, many talented patent attorneys who would much prefer to spend their days working directly with clients that present unique intellectual challenges and can really benefit from an attorney’s expertise, rather than filling in online forms, and dutifully following the detailed instructions of foreign associates for responding to examination reports.

The Same Tired Strategies Will Not Fix the Problem

My observation has been that the response of firm management – including the management of firms in listed groups – to the challenges of the Australian market is, first and foremost, to target attorney productivity. Typically this means setting higher billing targets, pressing for more accurate and detailed time recording, and/or curtailing the freedom of individual attorneys (including experienced senior practitioners) to exercise judgment over what time is chargeable to a client. In other words, doing precisely the same things that firm management has been doing since before I joined the profession (in 2002), and which has never previously resulted in any significant positive change! (As Albert Einstein never actually said: ‘insanity is repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results.’)The same old attorney-focused measures will not work any better now than they have in the past because the attorneys are not the problem. The market is the problem. The market for IP services in Australia is not growing. It is not becoming better informed or educated about the value of IP. It is not becoming more sophisticated. It is not becoming more willing to pay the full price that world-class IP expertise is worth. In fact, increasing micromanagement of intelligent, highly-educated, creative people (I am talking about patent attorneys here, in case you are confused), making them spend more time and effort on time reporting, and denying them autonomy in managing their interactions and relationships with clients may, if anything, have exactly the opposite of the desired effect. Heck, reasonably competent and worthwhile employees have quit perfectly good jobs over less!

At the same time, the marketing and business development side of firm activities largely continues along a well-trodden, but equally ineffective, path. Web sites of IP service providers are all the same. Feel free to check the links to the various listed group firms closer to the top of this article – structurally, they are virtually clones of each other, with similar sections for ‘people/professionals’, ‘industries/expertise’, ‘services’, ‘news/commentary’, and so forth. Everybody is competing for the same search keywords, and the same high-rankings in search results – from which the big winner is Google. All firms vie for sponsorship of, and dispatch attorneys to, the same conferences and industry events, often more out of fear that not being present will result in an opportunity (or an existing client) being lost to a competitor, rather than any expectation that significant new business will result from attendance. Very few people really want to talk to patent attorneys at these events – they know why the attorneys are there, and that it is not for the educational opportunities! These, and other ‘business development’ activities fall to attorneys who, in many cases, do not like doing them, are not especially good at them, and are rarely provided with the training and support they need to do them any better. If anybody were to conduct a serious cost/benefit analysis of these activities – fully accounting for the cost of attorney time and attention incurred against the value of new business acquired – they would scrap almost all of them, immediately, as a gross waste of valuable resources.

I know that there are people in marketing and business development at various firms who would take issue with some or all of the above. But my answer to them is simple. While individual firms may wax and wane from year-to-year, the fact is that over time, and across the profession, there has been no growth. There is no real growth (relative to population or GDP) in Australian filings. There is no real growth in revenue-per-attorney. There is no real growth in profitability. And if these numbers do not improve, then no amount of sound and fury will alter the fact that all of the marketing efforts amount to little more than running to stand still.

Conclusion – How Will QANTM+Xenith Tackle the Challenges?

The numbers in their annual reports over the past couple of years indicate that QANTM and Xenith each face similar challenges. Collectively, the (underlying) profit margin in their Australian IP services businesses sits at around 15% – far short of the 35% reported by IPH in its Australian and New Zealand IP services sector for FY2018. The proposed 55%/45% ownership split is broadly consistent with the overall revenues of each group, indicating this will be substantially a marriage of equals. The merged QANTM/Xenith group will still be, in terms of market cap, significantly smaller than the IPH group, however it would seem to make little sense for two such similar listed entities to continue to operate independently when whatever benefit there is to be gained from consolidation must logically be greater for a larger single grouping.But the merger will not do anything to change the underlying problems in the Australian market for IP services. And investors will still – quite rightly – want to know why they should own shares in an entity that posts profits in the range 10%-20%, when there is a business operating in ostensibly the same space that is more than twice as profitable. A couple of years ago my answer would have been that IPH’s business model is subject to higher risk, due to the potential for greater automation, competition, and price/margin reduction in substitutable transactional and administrative services such as patent filing. However, this has not come to pass, and I am now less convinced that it is inevitable, at least for the foreseeable future – it seems that the specialist filing service providers are just not making the inroads into their target market that might have been expected.

The main options for the merged group to increase profitability do not seem especially palatable. The first, of course, is to cut costs. According to the QANTM/Xenith investor presentation, there are ‘expected cost synergies of A$7 million per annum to be realised by the end of year three after completion of the merger.’ However, based on FY2018 revenues and expenses of the separate groups, this alone would increase profit margin only around three per cent (from about 15.4% to about 18.5%). Beyond this, salaries and related expenses being the main cost in a professional services business, further significant cuts would involve shedding staff. Notably, Xenith’s Chair, in the 2018 Annual Report, attributed the group’s poor performance, in part, to ‘excess capacity and suboptimal utilisation of professional staff’. Certainly, based on IPH’s numbers, it would seem to be possible for QANTM/Xenith to reduce staff numbers while maintaining its share of services provided to foreign clients. I expect that this would necessarily involve a reduction in work for domestic clients, however if this could be targeted to retaining higher-quality, more profitable, clients, then there may be a net positive contribution to the bottom line. Even so, this strategy implies an improvement in profit margin at the expense of shrinking the overall business, which is something that (I hope) the merged group is unlikely to find desirable.

The other option, then, is to increase revenue generated from existing resources. This is a difficult proposition. There is little that can be done to increase the size of the market for provision of services to foreign clients, which is driven from overseas, based largely on factors associated with national and global economies, and trade. Acquiring a greater share of the available foreign business from competitors is also challenging, given the extent to which it depends upon established relationships between attorneys. There is, as I have also noted, no real growth in the domestic market, with patent filings (for example) failing to keep up with either population or GDP growth. In any case, the figures I have presented suggest that this work is costly to acquire and retain, and does not make a sufficient contribution to profitability.

There is, however, another possibility. One thing that can certainly be said of the Australian domestic market is that it has massive untapped potential – if only Australian businesses could discover the value, and be convinced to invest at a commensurate price, in capturing, managing, and protecting their IP, particularly in technical innovations. How would this happen? I do not know (and, honestly, I am not hugely optimistic). But there is one thing I do know, which is that this market will not be tapped by continuing to do things the same way they have been done in the past. It will be interesting to see whether a merged QANTM/Xenith group will have the will and imagination to do something genuinely different to address the great malaise in the market with which it is faced.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment