For a long time now the number of patent applications filed in Australia has been increasing. For example, between 2009 and 2018 the total number of standard patent applications rose by over 25%, to nearly 30,000. This growth has been driven by foreign applicants, with the number of applications filed by domestic applicants being, at best, steady. There has, however, been a clear downward trend in provisional applications – which are predominantly filed by Australians, and represent the most common first-step into the patent system – where numbers have fallen by 22% over the same period.

For a long time now the number of patent applications filed in Australia has been increasing. For example, between 2009 and 2018 the total number of standard patent applications rose by over 25%, to nearly 30,000. This growth has been driven by foreign applicants, with the number of applications filed by domestic applicants being, at best, steady. There has, however, been a clear downward trend in provisional applications – which are predominantly filed by Australians, and represent the most common first-step into the patent system – where numbers have fallen by 22% over the same period.Not all of these patent applications – and especially provisional and innovation patent applications – are filed using the services of patent attorneys. For example, many inexperienced and impecunious Australian individuals and small businesses attempt to prepare and file their own applications, while some overseas applicants arrange their own filings, but are nonetheless required to provide an ‘address-for-service’ in Australia, which need not be a patent attorney.

It is therefore not immediately apparent from the overall filing numbers what impact these changes are having on the businesses of Australian patent attorneys. It is even less obvious whether there are any trends within the profession in relation to which firms are most affected by such changes. Conveniently, however, I have developed some data matching and analysis tools that enable me to identify filings according to whether or not they were handled by a registered Australian patent attorney or firm – as opposed to some other non-attorney agent – as well as which firms were responsible.

In this article, I will present the results of this analysis, some of which I found quite surprising. For example, I found that while the total number of provisional applications filed may have been in decline, this is almost entirely due to there being fewer self-filers, with attorney-filed applications remaining steady (though not showing any growth). I also found that, over time, there appears to have been a gradual shift by domestic applicants away from larger firms, in favour of smaller firms and individual attorneys. Further, I found that there has been a significant shift in the past few years, by both international and domestic clients, towards firms that remain privately held, at the expense of firms within Australia’s three publicly-listed ownership groups. I know that many private-practice attorneys will tell me that they already knew this, and I have certainly heard stories about client-transfers, however the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘data’. So now we have some data!

Definitions

Some definitions will be helpful for interpretation of the data that follows.When I talk about an attorney or an attorney firm I mean any individual who is registered as a patent attorney, or any private-practice IP firm that employs at least one such individual, according to the Register maintained by the Trans-Tasman IP Attorneys Board, as at February 2019. The significance of this definition is that under the provisions of Chapter 20 of the Patents Act 1990, registered patent attorneys are exclusively authorised to provide professional services relating to the drafting and amendment of patent specifications, and it is therefore effectively impossible to legally offer services, for financial gain, that include preparation and/or prosecution of patent applications without being registered.

Any person or organisation that is not an attorney or attorney firm according to the above definition, I would call a non-attorney agent. This includes self-filers (where the address-for-service recorded by IP Australia matches an applicant or inventor), and Australian residents who provide a local mailing address while not being an applicant themselves (one prominent example of which is the many innovation patent applications filed on behalf of Chinese applicants).

All of the following analysis is limited to applications for which the address-for-service is an attorney or attorney firm, i.e. cases in which the applicant has engaged the services of an Australian patent attorney. The numbers reported in this article are therefore lower than the overall totals that appear in some other articles on this blog, and in filing reports published by IP Australia and other organisations, which also include self-filings, and filings by non-attorney agents.

Further, I broadly divide applications into two classes. Applications without earlier priority are those for which no claim is made for the benefit of the filing date of a prior application, in Australia or elsewhere. In contrast with more common usage of this terminology in the patent profession, I include provisional applications in this category. The primary point of this definition is that in the overwhelming majority of cases, it captures applications where the Australian attorney or firm has been responsible for the preparation of a new, original, application, including drafting of the patent specification, regardless of whether this is then filed as a provisional application (which is the most common case) or as an innovation or standard patent application (which also occurs, to a lesser extent). Most (though not all) applications that do not claim an earlier priority date are prepared and filed on behalf of Australian-resident clients.

Applications with earlier priority are those innovation and standard patent applications – including national phase entries (NPE) of international applications filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), and divisional applications – for which the benefit of a filing date earlier than the actual Australian filing or NPE date is claimed. In most cases, the filing of such applications involves little or no new drafting work, and is a primarily administrative procedure. Over 90% of applications in this category are filed on behalf of foreign applicants, and in most of these cases the filing instructions come from a foreign attorney, with the Australian attorney having no direct communication with the ultimate client.

There is, therefore, a substantive distinction between applications with, or without, earlier priority claims, in the nature of work being entrusted to Australian patent attorneys at or around the time of filing and, in many cases, in the location of the ultimate client and nature of the attorney-client relationship. A far more significant role, mostly on behalf of domestic clients, is implied by filing of applications without earlier priority, which in many cases includes more general advisory services, in addition to drafting and filing of patent specifications.

Finally, in some of the following data and discussions I draw a distinction between firms that are now members of publicly-listed groups and those that have remained private. Some of the charts show results for both types of firms that extends back prior to the dates on which public listings and/or subsequent acquisitions occurred. These results must be interpreted in the intended spirit, i.e. as indicative of how past filings by private firms reflect the historical performance and current status of the firms now comprising the listed groups.

Total Filings by Attorneys

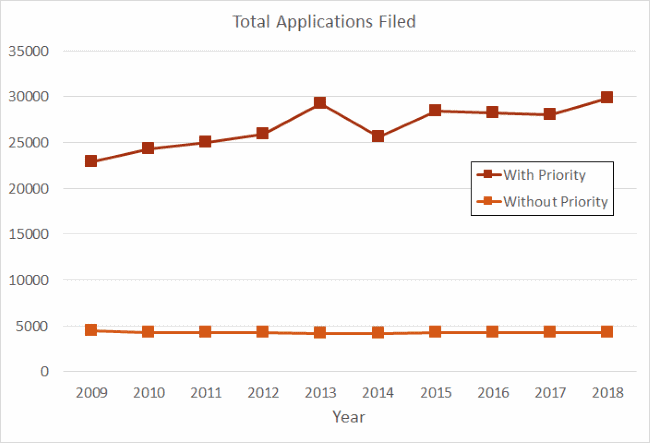

The chart below shows the total number of patent filings handled by attorneys and attorney firms, on an annual basis, over the decade between 2009 and 2018, separated into those with and without earlier priority claims. It is instructive to compare this data with the charts for all applications filed between 2008 and 2017 published in the ‘Patents’ section of IP Australia’s IP Report 2018. For applications with earlier priority, the numbers filed by attorneys are very similar to the total numbers of standard patent applications filed as reported by IP Australia. This is because the overwhelming majority of applications that claim earlier priority (most of which are filed on behalf of foreign applicants) are filed using the services of Australian patent attorneys.

However, the numbers of applications that are filed without earlier priority claims, i.e. those that are mostly drafted by Australian patent attorneys in my data, show very different characteristics to the overall total filings. The reason for this can be understood from the chart below, which shows numbers of applications without earlier priority broken down into provisional applications (a clear majority each year), standard patent applications, and innovation patent applications.

Looking particularly at provisional applications, IP Australia’s data shows a decline from 6,648 in 2008 to 5,182 in 2017. However, when the data is limited to those applications filed using the services of an Australian patent attorney, filings are almost flat at around 3,500 per year. We can therefore observe that almost all of the decline has resulted from fewer applicants attempting to prepare and file their own provisional applications.

This is a positive sign in one sense, since the evidence shows that self-filers perform extremely poorly in any subsequent efforts to obtain meaningful patent rights. However, the total lack of any growth whatsoever in professionally-prepared and filed applications (mostly, remember, on behalf of Australian clients) is just further evidence of what I have previously described as a malaise in the Australian market, and which I have blamed substantially on Australians’ lack of business sophistication when it comes to IP, about the poor appreciation in this country of the value of IP, and about the particular failures of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to identify, manage and protect their IP assets.

Are Firms in Listed Groups Losing Market Share?

As regular readers of this blog – and anyone interested in the Australian IP profession – will be aware, recent years have seen an upheaval in the structure of the profession in the form of companies listing on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) and acquiring multiple competing attorney firms, with the objective of raising capital to pursue new growth strategies in response to the challenging market, while also achieving efficiencies through sharing of back-office service costs (and, in one instance, actually merging previously independent firms). While the seismic activity continues, and seems certain to result in further change in the near future, there are presently three listed firm groups: IPH Limited (ASX:IPH) (listed 19 November 2014); Xenith IP Group Limited (ASX:XIP) (listed 20 November 2015); and QANTM IP Limited (ASX:QIP) (listed 31 August 2016).So, is this innovative growth strategy working? Well, while there is more to it than just patent filings (e.g. expansion into the Asia-Pacific region), on recent numbers it would appear that public listings have not been beneficial for Australian patent filings. The chart below shows annual filings of applications claiming earlier priority, broken down into totals for firms that now fall within the three listed groups, a grand total for all of these firms, and a total for all other ‘private attorney’-filed applications. While there has been significant growth in this category (from nearly 23,000 in 2009 to nearly 30,000 in 2018, driven entirely by foreign applicants seeking patents in Australia), it is clear that since 2015 the benefit of this growth has been entirely realised by firms that have remained private, with total filings by firms within publicly-listed groups having essentially flat-lined.

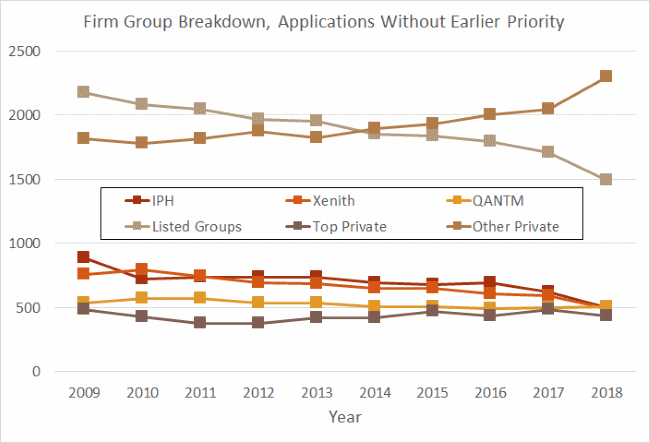

The results look even worse for firms in publicly-listed groups when it comes to filings without earlier priority, which I consider to be substantially a proxy for drafting and advisory work. The chart below shows annual filings of applications that do not claim any earlier priority, broken down into totals for firms that now fall within the three listed groups, a grand total for all of these firms, along with totals for all other ‘private attorney’-filed applications, now segmented into ‘top’ and ‘other’ private firms. The ‘top’ firms here are simply the three that made it into the top 10 in overall filings for 2018 (alongside the seven Australian-based listed group members), i.e. FB Rice, Phillips Ormonde Fitzpatrick, and Madderns. The ‘others’ are then all other private firms and individual patent attorneys.

The total number of applications without earlier priority has been virtually unchanged over the period shown, however the chart above clearly shows how market share of these applications has shifted away from firms that now fall within listed groups and towards privately-held firms and individual attorneys. In fact, the data shows that this is part of a longer-term trend by Australian-based clients, pre-dating the recent public listings and acquisitions, away from larger, often CBD-based, firms (represented primarily by firms within listed groups, and the top private firms), towards smaller and suburban practices (represented by the ‘other’ private firms and attorneys).

It is apparent, however, that while filings without earlier priority have stabilised in recent years for the top private firms, the decline has accelerated since 2016 for firms in publicly-listed groups, driven by falls within the IPH and Xenith groups. The beneficiaries of this trend have been the numerous smaller firms and attorneys, among which total filings have grown by more than 25% over the past decade.

Conclusion – What Does This Mean for the Listed Group Model?

One might conclude from the above data that the ‘experiment’ of publicly-listed ownership groups is showing distinct signs of failure. However, while I think it would be fair to say that there are no strong indications of success at this stage, the situation is probably more complex and nuanced than filing numbers alone would reveal.For one thing, we know that many of the originating (i.e. without-priority) applications by Australian applicants are one-off filings. For example, from 4,942 provisional applications filed throughout 2018, there were 3,250 applicants that filed only once. Two-thirds (2,158) of these had never filed before, of which most will never file again. For firms dealing with these applicants, there are significant costs associated with new client acquisition, and of advising people who are inexperienced with the patent system, and are often highly cost-sensitive. Whatever benefits there may be in dealing with such clients (and I am certainly not saying there are none), they can be the hardest to work with, and are often the least profitable. So if this makes up the majority of the work that has been migrating to smaller private firms, then this might actually be to the financial benefit of firms within the listed groups in the longer term. Larger firms would, arguably, be quite justified in directing their marketing and business development activities towards lower-maintenance, and more profitable, clients.

Indeed, while IPH reported a fall in profit margins in its Australian and New Zealand IP services business between FY2017 and FY2018, both Xenith and QANTM reported modest increases in profitability (excluding a one-off ‘impairment charge’ of A$20.7 million taken by Xenith in respect of the carrying value of its Griffith Hack and Glasshouse Advisory businesses). Xenith firms, in particular, were experiencing a decline in ‘without priority’ filings, and no growth in ‘with priority’ filings during this period, according to the data above. And, in its recent half-yearly results (see IPH News & Announcements for details) IPH reported a 4% growth in underlying earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) in its Australian and NZ businesses, despite a 1% decline in revenues. Clearly, then, filing numbers alone do not tell the full story.

Nonetheless, the numbers do reveal an inexorable shift in the market for patent attorney services in Australia. It will be interesting to follow how far this shift goes, and the impact of an all-but-certain consolidation of the three listed groups into two within the coming months.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment