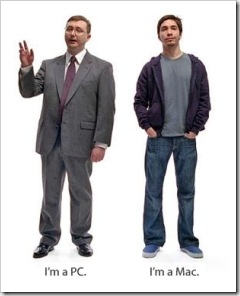

In the first part of this series of articles we introduced the current state-of-play between Apple and its Android rivals, particularly Samsung.

In the first part of this series of articles we introduced the current state-of-play between Apple and its Android rivals, particularly Samsung. This is not the first time that Apple has engaged in litigation with a competitor over who would gain a dominant place in consumers’ lives.

We are all familiar with the sometimes bitter rivalry between Apple and Microsoft. But it is worth looking back at history to see what it might tell us about the origins of Apple’s apparent great animosity towards Android.

Background – the struggle for control of the desktop

Apple is no stranger to litigation over IP rights – or to accusations of copying. In 1982 Apple filed a copyright complaint against Franklin Computer Corp, alleging that Franklin’s ACE 100 personal computer included unauthorised copies of the Apple II operating system and ROM. In those days the reach of copyright law in relation to computer software was unclear and it was only on appeal that Apple was vindicated, with the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ruling that executable object code, as well as human-readable source code, was protected by US copyright law.More famously, in 1988 Apple sued Microsoft and Hewlett-Packard, alleging that Microsoft Windows and HP’s NewWave software violated Apple copyrights in the Macintosh user interface. As would later be the case with Samsung, Microsoft was a company with which Apple had a complex relationship. Microsoft had been the first third-party applications developer for the Macintosh, with its Word and Excel products, which had not only helped to make Apple a pioneer in desktop publishing, but also launched Microsoft into the applications software business. Apple had licensed aspects of the Macintosh GUI to Microsoft for use in its Windows 1.0 software in exchange for an additional two years’ exclusivity of Excel on the Apple platform. But – in a pre-echo of negotiations with Samsung 25 years later – the licence did not cover some of the features, such as overlapping windows, which gave Apple’s interface an aesthetic edge over other window-based interfaces, including the Xerox PARC Alto GUI, which had notoriously inspired Apple. So when this, and other, unlicensed features appeared in Windows 2.0, Apple filed suit against Microsoft.

By 1997 Apple had lost the "look and feel" copyright case. However, significant tension with Microsoft remained, with various disputes and potential new litigation lingering. Apple was in disarray regarding the direction of its operating system development and Microsoft was refusing to give a commitment to the development of Word and Excel for the uncertain future MacOS platform. At the same time, the US Justice Department was threatening antitrust action against Microsoft, with the potential to force a breakup of the company into a number of smaller divisions with reduced market power. This situation had come about entirely during the period of Jobs’ enforced exile from Apple. The original licensing deal and lawsuit were conducted on the watch of then-CEO John Sculley, and relations with Microsoft deteriorated still further under successors Michael Spindler and Gil Amelio.

The complexity of Apple’s relationship with Microsoft was paralleled over the years by that of the companies’ protagonists, Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. Despite intense rivalry, and almost diametrically opposed philosophies of life and business, the two men always shared a grudging respect for one another. So when Steve Jobs returned to Apple and Amelio was ousted in 1997, one of Jobs’ first phone calls was to Gates. Almost immediately they were able to find common ground – Apple had got Microsoft into the applications software business and the Microsoft developers still liked working on the Mac platform. While Jobs maintained that Microsoft was infringing on various Apple patents and other IP rights, each agreed that the dispute had become unproductive and potentially damaging to both companies.

Jobs proposed to simplify the terms of a settlement to just two requirements: a commitment from Microsoft to continue developing software for the Macintosh and an investment that would ensure that Microsoft had an ongoing stake in Apple’s success. The final deal – reached in just a few weeks, after years of intractable antagonism – saw Microsoft agree to continue development of Office for the Mac and to invest US$150 million in exchange for non-voting shares in Apple, while Apple would ship its MacOS with Internet Explorer as the default browser.

Ideological differences – closed v open

Among the differences distinguishing Jobs’ approach to product design from that of Gates was a fundamental opposition between closed and open systems. While advocates of the free and open source software (FOSS) movement would no doubt take issue with the assertion that Microsoft’s Windows is an open platform, in all relevant senses it is, and certainly by comparison with Apple’s platforms. The difference between Microsoft’s brand of openness and that of open source software is principally price. Licences have always been broadly available to anybody wishing to run Microsoft operating systems and willing to pay the asking price. Microsoft has even licensed source code to various parties (e.g., Citrix Systems Inc) in appropriate circumstances. As a result, Windows is even more ubiquitous than its dominance of the desktop market would indicate. It powers over one-third of all servers and Windows variants can also be found in a wide range of embedded systems applications, from test and measurement equipment to automatic teller machines and point-of-sale systems, from display signage to in-vehicle automotive systems. Certainly, Windows is not free – either as in free beer or as in free speech – but by any measure it is a platform open to all comers on largely non-discriminatory terms.This is in stark contrast to the Apple philosophy. Jobs always favoured closed systems in which everything was vertically integrated and completely within Apple’s control. In the early days, this meant having control over both the hardware architecture and the software. In the current environment, Apple controls everything – the silicon (i.e., the A-series processors), the device hardware (iMacs, iPods, iPhones and iPads), the operating systems (MacOS and iOS), the user interface (e.g., the iPhone and iPad touch-screens and home pages), the content (e.g., through iTunes), the network storage and computing platform (iCloud), and even the third-party applications permitted onto its mobile devices (most notoriously, its refusal to allow Adobe’s Flash to run on the iPhone or iPad).

The one time Apple deviated from its closed approach, when first Spindler and then Amelio allowed the Macintosh operating system to be licensed to clone manufacturers, it proved to be a disastrous strategy. Apple made only US$80 in licence fees from each Macintosh clone that was sold, but the clones were cannibalising Apple’s own computer sales, on which it made up to US$500 on each purchase.

Of course, things might have been different if Apple had licensed the Macintosh software to other hardware manufacturers from the outset. But unlike Gates with Microsoft, Jobs never saw Apple as a software company. All he ever wanted to do was to create “great products”. While the IBM PC architecture enabled users to get inside the box and add new hardware interfaces – creating a whole new market for third-party hardware devices – Jobs was so strongly opposed to allowing anybody to tamper with the Macintosh’s innards and interfere with Apple’s total control that he insisted on using unique screws which required a special tool and could not be removed with a regular screwdriver. The Macintosh was not made for hobbyists or hackers, it was made for ordinary consumers; and Jobs wanted to ensure that Apple provided a consistent, controlled, non-threatening and satisfying end-user experience. With Jobs’ triumphant return to Apple in 1997, the focus of the company went back to creating a small number of great, vertically integrated products with simple and friendly interfaces for the masses.

There can be no question that the open model won the battle for supremacy on the desktop – the most generous estimates give Macintosh products little more than 5% of the global market. However, this was certainly not because the products of the open model provided a better user experience. Almost every complaint levelled at the so-called Wintel PC platform – complexity, bloatedness, instability, inconsistency – has its origin in support for open interfaces. Complexity is a consequence of supporting the flexibility required for a huge and unpredictable range of hardware platforms and uses. Each new version of Windows has had to maintain compatibility with countless thousands of legacy applications and systems. And – lacking control over third-party hardware and software, or the infinite variety of system configurations that users can create – there is no way for Microsoft to guarantee that any particular system will be stable, reliable or useable.

Apple’s closed platform has allowed it to keep its products simple, stable and elegant, and many of its customers love it for this.

Coming up in Part III we will fast forward to the current mobile device disputes, and look at how Apple is deploying its IP assets in the struggle for the hearts and minds of consumers.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment