In the previous article in this series, we looked back at the struggle between Apple and Microsoft for ‘ownership’ of the desktop. We argued that this was a confrontation between opposing ‘closed’ and ‘open’ models – not only of the software and hardware platforms, but also of the fundamental way in which the two companies do business.

There is no question that Microsoft was the clear winner, despite some of the uglier consequences of trying to support a huge range of different hardware and software configurations. Yet despite this loss, Apple – and Steve Jobs – have persisted with the closed platform model. So what did they learn from history?

The battle for hearts and minds

Apple’s current IP litigation strategy is not just about the alleged infringement of Apple’s IP rights by a few competing products. It is a fundamental battle which could determine whether the closed or open models will dominate the market for mobile devices. In one corner is Apple, with its vertically integrated model – the iPhone, the iPad, the iTunes store, the Apple Apps Store and iCloud. In the opposing corner is Google with its open Android platform, available to any device manufacturer that wishes to use it.What Apple apparently learned from its experience on the desktop was not that open is superior to closed, but rather that a different strategy would be required to keep the open competitors at bay. Considering the history, and his infamous volatility, it is understandable that Jobs’ widely reported “thermonuclear war” rant to biographer Isaacson was directed at Google – who “wholesale ripped us off” – and Android – a “stolen product” – which he saw as the equivalents of Microsoft and Windows in the current era. However, Apple’s lawsuit at the time was against HTC, not Google. Subsequent suits related to Android-based devices produced by Motorola, and then Samsung.

Samsung and HTC also market devices based on Microsoft’s Windows Phone OS, yet these devices have not been targeted by Apple. Indeed Microsoft, for its part, has recently taken a different path in relation to its IP assets. It employed Marshall Phelps as corporate vice president for IP policy and strategy. Phelps had famously spent 28 years at IBM, where he was responsible for convincing the company’s management that its IP portfolio was an asset that should be valued and licensed appropriately, rather than merely being traded on a like-for-like basis. During his time at Microsoft, Phelps transformed the company from its fortress approach to IP into an organisation which had entered into over 500 technology agreements with partners and competitors. It has been reported that, after finalising patent licence agreements with HTC and others, Microsoft now generates more income from the sale of Android-based devices than it does from its own Windows Phone OS.

Microsoft, it seems, is no longer a frontrunner in the battle for hearts and minds of consumers. No doubt it considers its Windows Phone to be a great competitive product, but it is also deploying its sizeable IP portfolio to ensure that whatever device and OS the consumer chooses, Microsoft receives its share of the rewards for the innovations it has contributed to the sector. In other words, Microsoft is moving towards an open innovation model – even recently submitting code to long-term foe, the open source Samba Project – while Apple, true to form, remains steadfastly closed.

Apple’s IP deployment

Apple’s lawsuits against the alleged “slavish copying” of its products are based on various patents, registered designs (design patents in the United States) and claims of trade dress infringement, or unfair competition, in combinations that vary in different jurisdictions.Apple’s competition and trade dress claims appear, on their face, to be of dubious merit. If it were dealing with manufacturers of counterfeit products – and such things do exist in some parts of the world – then Apple’s assertions that the accused products are designed to fool consumers into making purchases in the mistaken belief that they are buying Apple products might be more convincing. But it requires positing an extremely unsophisticated consumer to conclude that a purchase of such substantial value could be completed without awareness of the origin of the product. All of the relevant devices are quite clearly branded, and companies such as Motorola, Samsung and HTC have absolutely no interest in trading off Apple’s brand or reputation at the expense of their own.

Of course, there is no question that various competitors have intentionally imitated certain design and functional features of Apple’s products on the basis that they are particularly useful, effective and/or attractive to consumers. However, in the absence of some protectable and enforceable IP right, such imitation is part and parcel of free competition. As Jobs is reported to have said: “Picasso had a saying – ‘Good artists copy, great artists steal’ – and [Apple has] always been shameless about stealing great ideas.” For Jobs, perhaps ‘stealing’ was justifiable in the service of great art, but not in the production of what – to him, at least – were inferior imitations. He was not entirely unjustified in his confidence in his judgements. As even Bill Gates had to admit during one public appearance: “I’d give a lot to have Steve’s taste.”

With regard to the design-based claims, Apple has already achieved some success in Europe, with a German court having issued a preliminary injunction against Samsung’s Galaxy Tab 10.1 on the basis of a registered Community design relating to the appearance of the iPad 2. However, the validity of the design registration has yet to be established, and in the meantime Samsung has bypassed the injunction by making a few tweaks to the exterior design of its product.

The very purity and simplicity of Apple’s designs, which make them so appealing to consumers, may be a weakness when it comes to obtaining and enforcing associated IP rights. The characteristic features of the design of the iPad 2, for example, are its slim profile and sleek, round-cornered rectangular design. Such functional minimalism does not make for strong, or broad, design protection. The scope for differences from the prior art (including, in some of Samsung’s defences, fictional designs appearing in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey and television series Star Trek: The Next Generation), and for competitors to innovate distinctive yet equally functional designs are limited. And unfortunately for Apple, designs law protects only what is visually perceptible, not the emotions that a product might elicit.

Patents

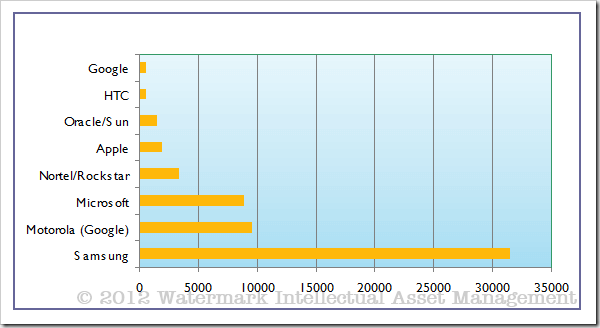

Apple’s strongest assets in its IP litigation will therefore most likely prove to be its patents. There is no question that Apple holds some potentially significant patents, particularly in the areas of touchscreen technology and user interfaces. Two of these patents effectively delayed the launch of Samsung’s Galaxy Tab 10.1 in Australia for four months in 2011. However, Apple’s patents will need to be of great strategic significance if they are to overcome the superior numbers of its competitors’ portfolios.The results of a search for patents relating to mobile device technologies and software are shown in the chart below. Each bar represents the number of distinct families of patents and applications held by the respective proprietors, as identified in a search based on relevant classes of the International Patent Classification system in combination with keywords such as cell, mobile, handset, phone, tablet, touch screen, touch pad, handheld, portable, telecomm, device, terminal, and combinations and variations of these terms. In total, 58,060 families were identified in the names of the selected proprietors.

The search identified 1,941 distinct patent families owned by Apple. This number will be augmented in some manner by Apple’s share in the 3,424 families owned by Nortel and acquired in June 2011 by the Rockstar Bidco consortium (Apple, Microsoft, Research In Motion, EMC, Ericsson and Sony). However, it is still far short of the 8,887 patent families held by Microsoft, the 9,582 held by Motorola Mobility (to be acquired by Google) or the massive 31,524 held by Samsung.

With many of Apple’s major competitors having much larger patent portfolios, Apple would seem on the face of it to be substantially out-gunned. In Part IV we will look more closely at why appearances can be deceiving, and how there is more to a strong patent portfolio than sheer quantity.

Before You Go…

Thank you for reading this article to the end – I hope you enjoyed it, and found it useful. Almost every article I post here takes a few hours of my time to research and write, and I have never felt the need to ask for anything in return.

But now – for the first, and perhaps only, time – I am asking for a favour. If you are a patent attorney, examiner, or other professional who is experienced in reading and interpreting patent claims, I could really use your help with my PhD research. My project involves applying artificial intelligence to analyse patent claim scope systematically, with the goal of better understanding how different legal and regulatory choices influence the boundaries of patent protection. But I need data to train my models, and that is where you can potentially assist me. If every qualified person who reads this request could spare just a couple of hours over the next few weeks, I could gather all the data I need.

The task itself is straightforward and web-based – I am asking participants to compare pairs of patent claims and evaluate their relative scope, using an online application that I have designed and implemented over the past few months. No special knowledge is required beyond the ability to read and understand patent claims in technical fields with which you are familiar. You might even find it to be fun!

There is more information on the project website, at claimscopeproject.net. In particular, you can read:

- a detailed description of the study, its goals and benefits; and

- instructions for the use of the online claim comparison application.

Thank you for considering this request!

Mark Summerfield

0 comments:

Post a Comment